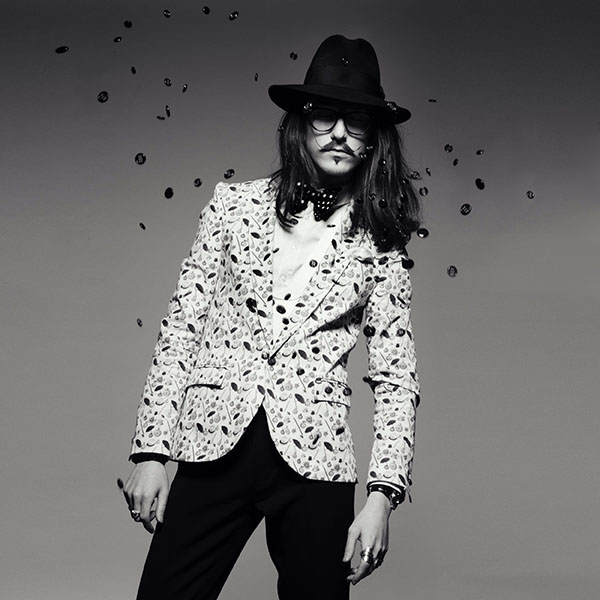

Old is the new new

Tailor Joshua Kane taps into cultural references from across the centuries

A friend recently posted photos of her weekend to her Facebook wall. Nothing spectacular about that, you are right to say. Her weekend was spent at the Rewind Festival, three days of bands and singers from the 80s. Again, standard social media fare.

I worked out that in 1989, she was 10. Therefore, her experience of pop culture from that decade was mostly as a toddler. She is reliving a culture that, from her personal perspective, didn’t exist in any depth. Her access to that era came later – radio stations playing hits from the 80s, being pissed in retro nightclubs such as Reflex, and a “scraping” of that era’s surface elements from popular television.

While I was swift to question the legitimacy of her attendance in my mind, my conscience then questioned my own questioning, as it were. Who am I to judge what she can and cannot do?

After all, when I was a wee imp myself, my favourite band was the Beatles (who split before I was born) and I actively participated in the early-90s rebirth of flower power by buying a tie-dye T-shirt and a double-album called “The Summer Of Love”, featuring songs from between 1967 and 1970, again, all before my birth.

The fact of the matter is that the gates to entering a cultural period are now open to all. Look at the incredible mass adoption of the thirties and forties: burlesque, swing dancing, and long, flowing skirts.

The mass re-emergence of such cultural phenomena irked me for a while. What is the next “wave” and when will it happen? As I get older and more of a grumpy bastard (naturally), what the hell are “the kids” doing? Why aren’t they making me angry with the way in which they dress, or the music which they create? Where are the new MDMA-charged raves, acid-charged summers of love, or speed-charged mods-and-rockers punchups?

Why are the kids of today so culturally fucking placid?

Of course, they’re not placid at all. Quite the opposite. The reason? The same one as many other contemporary phenomena. The Internet.

By way of universal access to information and knowledge, we have universal access to the past. There is no gatekeeper. Taking cultural ephemera from the past, thankfully, ain’t what it used to be. Where it used to involve ordering albums from the Our Price back catalogue, browsing charity shops for genuine old clothing and magazines, and connecting with like-minded individuals through fanzines, it now involves spending quality time with YouTube and a few choice online forums in a setting of your choice.

Such access has facilitated the re-appropriation of old cultural artefacts into neo-ephemera. The late 19th and early 20th century, what we term the Victorian era in the UK, gave men long but neat beards. That style is now, of course, the Hipster Beard, born in Portland, Oregon and has spread around the world to Portland, Dorset and beyond. If it wasn’t for the Internet and the ability to scrape culture from practically any period in time, the Hipster Beard would have remained in the past.

And look at what else we’re pulling up to the present day. Jump suits. Big earrings. Retro trainers such as Adidas Stan Smith and even Hi-Tec Silver Shadow. Casio digital watches. The list goes on and on. It gives all of us the individual right to wear just what the hell we like – because we have access to its reference points of cultural origin.

The ability to take any element of historic culture and re-interpret it to the contemporary era is like nothing that we have ever seen before. Anyone, regardless of colour, creed, gender, or practically any other attribute has unbridled access to copious historic culture.

The result is that each time we’re taking from the old, we are, in fact, creating something new. It is the Renaissance, subjectively re-interpreted for each and every one of us. As the late, lamented Malcolm McLaren said in 1990, “Appropriation [is] at the source of any artistic creation, no matter what”.

It makes everything old, new.

It makes nothing old any more.

If postmodernism is defined as a self-constructed reality transcendent of shared human understanding, then it has truly arrived.

Words: Paul Squires