Bailey sprinkles some stardust over the dank winter months with this important retrospective

Kate Moss, 2013

With tousled mane, Kate Moss guards the entrance to David Bailey’s Stardust, newly opened at the National Portrait Gallery. Her gaze is both sultry and defiant – the gaze of a model turned Contributing Editor of British Vogue, the gaze of a woman whose beauty defines an age. Images of the private view of the exhibition show the photographer himself – a cheeky glint in his eye, wearing a handkerchief around his neck and Dickies trousers – receiving a kiss from Moss on one cheek and Jerry Hall on the other, both towering over him.

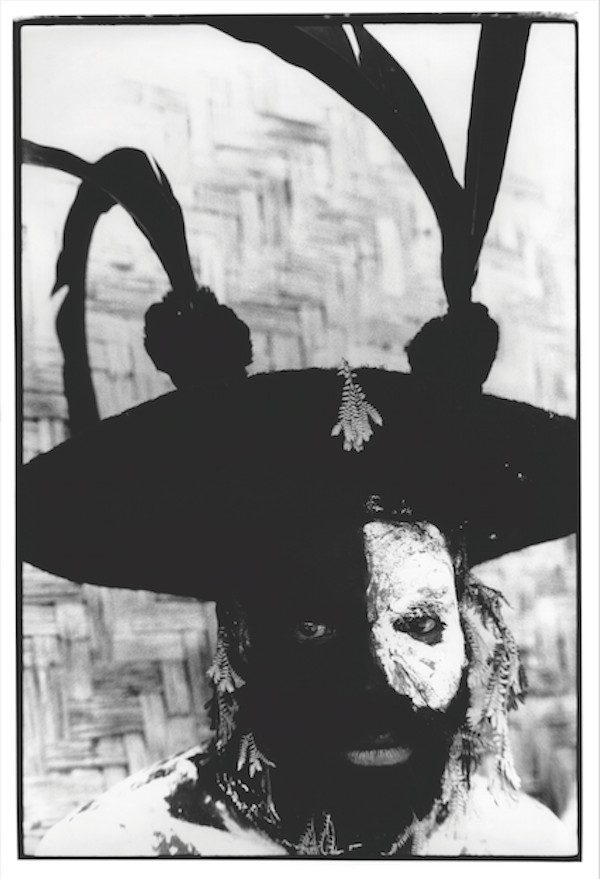

Kate Moss, like so many of Bailey’s women, is the face of her time. Beside that face we have Sixties waif Jean Shrimpton, Catherine Deneuve, Penelope Tree, Marie Helvin, Jerry Hall (in lurid Eighties colours) and a whole room dedicated to his wife, the model Catherine Dyer. But whilst Bailey’s fashion photography is a real treat, more unexpectedly delightful is his photojournalism, from his travels to India, Africa, Australia, and Papua New Guinea, and his gruelling shots of famine and war refugees in Ethiopia and Sudan.

It seems fitting that Bailey should return to The National Portrait Gallery for his retrospective, as it was the first gallery to show his photographs, at an exhibition called Snap in 1971. Bailey has curated this exhibition himself, choosing over 250 portraits which occupy the whole of the gallery’s first floor. It is the full Lucian Freud/ David Hockney treatment, and a testament to the 75-year old photographer, whose career has spanned half a century and a whole lot of pop culture revolution. The exhibition is made up of clusters of images arranged around the themes of fashion, travel and family. Silver gelatin prints and iconic black-and-whites hang alongside colour photographs, formal commissions beside images taken on a camera phone and candid family photographs.

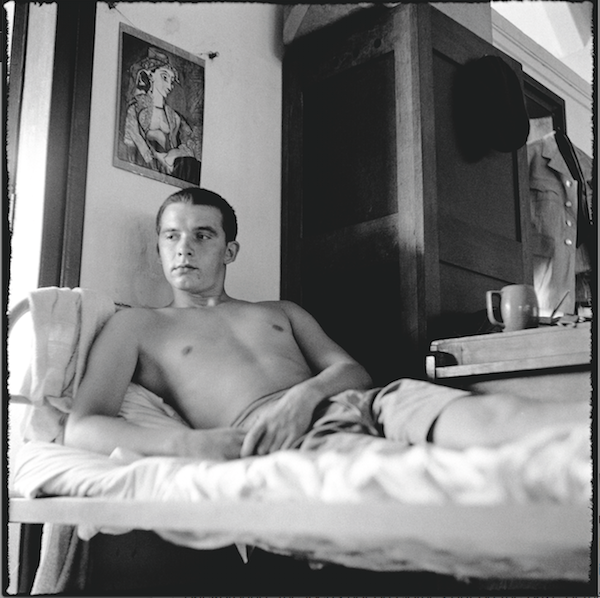

Self portrait

Bailey first established a name for himself with his work for Vogue in the 1960s. He is credited with discovering the model Jean Shrimpton, catapulting her to fame after an iconic shoot in New York in 1962. Here she is, kohl-eyed, the defining look of a generation. There are portraits of Mick Jagger (who Bailey first met when Jagger was dating Shrimpton’s sister), The Rolling Stones and a Surrealist Mia Farrow, floating head on a sea of clouds. The portraits are instantly Bailey’s; medium format, crisp white background, the focus not on clothes but on the gaze of the sitter. Often talking to his subjects for an hour or so before laying a finger to his camera, Bailey teases his subject out; none of them looks withdrawn. There is an ease to his portraiture, a sense of humour. His louder portraits are almost flippant.

Another cluster shows the tribe of Diana Vreeland: Vivienne Westwood, festooned in burgundy satin; Alexander Mc Queen, jumping and jubilant in a kilt. And from fashion to the visual arts we have photographer Man Ray in profile, Richard Hamilton (himself the subject of a retrospective opening at the Tate Modern this week), Andy Warhol and a selfie with Salvador Dalí.

Jerry Hall and Helmut Newton, 1983

Mick Jagger

Bailey’s Box of Pin-Ups from 1965 is on display, with images of John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger in that fur hood. It is like a who’s who for London’s Swinging Sixties – including the notorious gangsters, the Kray brothers. Bailey documented life in East London, site of his childhood, for the feature “East End Faces” for The Sunday Times Magazine in 1968; we see the streets of Bethnal Green, Brick Lane and Whitechapel, with sisters in shift dresses drinking sherry in their front room and children running amid piles of rubble leftover from the bombing of the East End in the Second World War. It is a fascinating glimpse at the daily life of a city that has now changed almost beyond recognition.

Best of all, Bailey has an eye for a character. Take “Prince Albert” from his Democracy series, a man so covered in tattoos and piercings that his own skin is no longer visible. From 2001 to 2005, Bailey photographed visitors to his studio, naked, at a uniform distance of six feet from his lens. The unedited images are shown with wonderful frankness.

But beyond the documentation of celebrity culture and the quirks, there is an unexpected side to Bailey. In an intensely strong, affectionate and personal acknowledgement, a whole room is dedicated to the photographer’s fourth wife, the model Catherine Dyer, whom he met in 1983 and married three years later, and their three children – Paloma, Fenton and Sascha. The images of Catherine are very small, hung in a crowd on the wall. She is captured both as a fashion model and as a mother, and pictures of her in lace brocade hang alongside pictures of her giving birth.

Just as surprising are the pictures of Bailey’s travels, of much-visited India and the tribes of Africa and Papua New Guinea. Portraits of tribal elders and of holy men are a world away from the sharp-suited celebrities of the Sixties, yet there remains the sharpness of gaze, the brazenness, that runs throughout his work. There are pictures from Sudan and Ethiopia, refugees fleeing from famine and civil war and starving children with distended stomachs. These are difficult to see after the sudden-seeming frivolity of celebrity culture, but they demonstrate the skill with which Bailey works across such a range of subjects.

Bailey is occasionally criticised for lack of depth and for failing to bring out the interiority of his subjects. This is to do the photographer an injustice – it is not what he is about. Often brazen and flippant, his photographs capture the very era in which they were taken. The war-wrecked streets of East London give way to glamour and the rise of celebrity culture, but even there can be found surprising and hidden depths.

Bailey’s Stardust, sponsored by Hugo Boss, is on at The National Portrait Gallery until June 1.

Words: Harriet Baker