Following critical success at the Edinburgh International Film Festival this week, actor and screenwriter Leeshon Alexander talks to Mary-Jane Wiltsher about his harrowing fact-based prison film We Are Monster…

At 3.30am on a February morning in 2000, inside the walls of Feltham Young Offenders Institution, violent racist Robert Stewart bludgeoned his 19-year-old cellmate Zahid Mubarek to death. Mubarek was just hours away from release, at the tail end of a 90-day sentence for stealing £6-worth of razor blades. Despite demonstrating a vicious undertow of institutional racism and gross negligence in Britain’s prison systems, the public inquiry spurred by the brutal episode wavered and sank into obscurity, with none of the named 14 prison officers involved receiving disciplinary action.

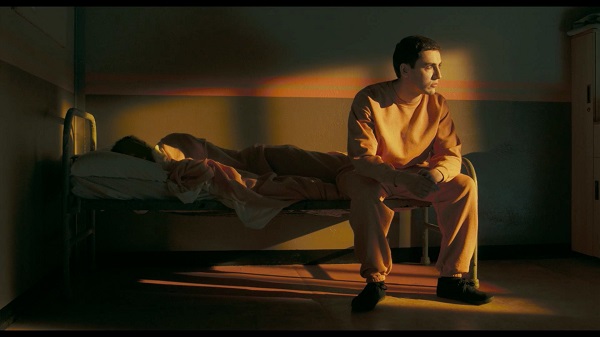

The low-budget drama We Are Monster, starring and written by emerging talent Leeshon Alexander, and directed by Antony Petrou, recalls the case to the spotlight, upturning Feltham’s scabby underbelly with gritty sincerity. Premiered at the Edinburgh International Film Festival earlier this week and nominated for the Michael Powell Award, the film is a two-fold success, skilfully balancing an intensive psychological exploration of a killer’s warped mind with languid arthouse cinematography. The film’s concoction of lingering, scene-setting shots, sullen silences and unflinching dialogue, all washed over with a bruised colour palette, carries echoes of This Is England. It’s an impressive achievement for the until now lesser-known Alexander, who studied business and accounting at Liverpool University before undertaking a year at London’s ALRA Drama School.

At the blackened heart of the narrative is Alexander’s dual performance as Stewart and his goading internal voice, physically manifested here in order to cement Stewart’s motivations and provide a backstory. Granted, it’s a theatrical device which occasionally jars with the film’s realism, but bar a few moments of over-acting it’s deftly handled, building to a devastating climax.

How did the concept for the film and your collaboration with Antony Petrou come about?

Antony and I are really close friends and had previously worked together on Senet [2012] but couldn’t quite finish the film because we didn’t have the money. I was trying to forge a career and I liked writing, so having had that experience I thought: ‘Okay, I‘m going to make my own smaller scale film.’ I asked my dad to help find me a story. I wanted something socially and politically relevant, and I remembered the case as soon as dad mentioned it. The research process took about three months in total and I spent six weeks writing the screenplay.

So you wrote the part with yourself in mind?

Absolutely. It was a calling card, if you like. I became really involved. Initially it was about making this great artistic movie, but then I realised how morally important the film was as a portrayal of the prison system.

The film’s languid cinematography, carefully composed colour palette and dialogue-free sections are a far cry from your archetypal prison drama. How much creative license does the film take?

Yes, it’s unashamedly arthouse, but it’s not like we could make Starred Up [British prison drama, 2013] because this was a true story and we couldn’t fictionalise it in any way. Our primary focus was to make the case blow up in the public eye again – that’s the reality of the type of film we wanted to make, and if we’d tried to create something bigger it wouldn’t have had the same feel. In terms of events, everything in the film really happened: Zahid reporting back on Robert’s behaviour, the guard spilling the toilet roll across the floor on finding Zahid’s body, Robert and Travis stabbing their arms, Robert scratching his own face out of a photo because he thought he was ugly… that’s all true. Robert’s letters in the film are verbatim, he actually wrote those kind of things, it’s all there on paper. We included little visual references to link back to Robert’s childhood, like the projector mechanism.

When did you decide that Stewart’s inner voice would have a physical form?

We needed Robert’s inner voice to flesh out the film and I talked to a criminal psychologist about it, who said it made perfect sense that there would be a ‘double’ figure, given Robert’s behaviour and mindset. In many ways, Robert’s double is a perfect manifestation of himself – he has smoother skin, his voice is clearer and stronger, he’s more articulate. It was a way of showing that, in Robert’s head, there was an odd method to the madness.

Is it true that Petrou kept you apart from Aymen Hamdouchi, who plays Mubarek, until your first scene together?

That’s right, we didn’t meet until then – we weren’t allowed to talk to each other until the scene where I first walk into the cell. It was a great way to create authentic tension. After the scene, I asked if I could go and give him a hug!

In reality, you look completely different to Stewart – tell us about your physical transformation for the role?

I had to exfoliate my face and avoid the sun, wax my chest and arm hair, and lose weight – no beer or carbs! We used make-up to create the shadows under my eyes and make my skin look bad. I’m not interested in playing someone who’s just like me, I like the idea of those transformative roles.

What’s next – are you working on another project at the moment?

I’m still feeling my way, really. There are three more scripts that I’ve written, and I’m keen to work with Antony again in the future. A lot of people have asked if I’d make the move into directing myself – I’d probably give it a try, but I’m an actor first and foremost, and a writer second.

You’re a good example of a creative self-starter in a competitive industry – what advice would you give to other young screenwriters and actors?

Be ambitious. Go for things that are bigger than what people will assume you can do. Also, if you’re a writer, learn how to direct and produce, and vice versa, you’ll get on better with the people you’re working with and have a greater understanding of what they do. Work hard. Persevere. You’ll hear ‘no’ a lot, but keep plugging away. Have drive.

We Are Monster received its world premiere at the Edinburgh International Film Festival on June 20.

The Zahid Mubarek Trust [ZMT] is an independent charity which serves to benefit society by advocating for reforms and challenging discrimination within the criminal justice system. They accomplish this by providing evidence-based intervention to inform national policy and grassroots procedures. With an impetus provided by the death of Zahid Mubarek, the Trust fulfils a unique role in addressing inequality.

To support the Zahid Murbarek Trust, visit the website