★★★★☆

Given the sheer abundance of celluloid focused on Muhammad Ali, does the world really need another film about ‘The Greatest’? On this evidence, yes. Bill Siegel’s The Trials of Muhammad Ali comes out of the corner with a solid, meticulously constructed documentary that delivers a breathtaking final knock-out. The film doesn’t just earn a place in the catalogue of previous Ali movies; it provokes the question of how such a crucial period in Ali’s life – his drift into separatist Islam, refusal of the Vietnam draft and subsequent professional exile from the sport between 1967 and 1971 – has not been given this quality of examination before.

Although focused on the most recognisable boxer in history, this isn’t a documentary about boxing, but a different sort of fight. As the film begins we are plunged straight into an atmosphere of treacherous political uncertainty, with peaceful student protests ripped apart by excessive police brutality and the civil rights movement finding its feet. Olympian gold medallist Cassius Clay gets swiftly swept up into the separatist rhetoric of the Nation of Islam. In the 1950s, Elijah Muhammad and the NOI had mentored a certain young man by the name of Malcolm Little, who denied the civil rights movement’s call for integration in favour of segregation at any costs. Now Malcolm X becomes mentor to Cassius Clay’s dual journeys: becoming Heavyweight Champion of the World, and undergoing a religious revolution of his inner self.

In 1954, we see Clay’s title shot lined up against the seemingly unbeatable Sonny Liston. The event is nearly derailed when Clay insists on fighting under his new Muslim name Cassius X; but although he is forced to capitulate by the intransigent organisers, he scores a sixth round knockout, and is subsequently bestowed a higher-status moniker from the Nation of Islam: Muhammad Ali.

The bulk of the film focuses on Ali’s refusal to join the Vietnam draft in 1967 and his subsequent battle to survive the backlash. Ali insists that “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger,” but this matters little to the US Government. Ali is stripped of his title and sentenced to five years incarceration, a $10,000 fine and a three year boxing ban. Ali launches an immediate appeal, but the authorities make sure that it will take three years just to process.

And this is where we really start to realise just how hard it must have been for Ali to survive. How does a boxer provide for his family when he’s not allowed to box? Ali earns some cash speaking at campuses and colleges across the States, but the strain is always close to the surface. In one scene, having been questioned on Islam for too long, Ali snaps at his student audience. “You my enemies. My enemies the white people, not the Viet Cong. You my opposers when I want freedom. You my opposers when I want justice. You my opposers when I want equality. You want me to go somewhere and fight but you won’t even stand up for me at home.”

The documentary features a huge amount of never-before-seen archive footage and the story is told through the words of Ali himself and his closest comrades, rather than the usual cast of questionable bit players. Siegel has lined up a who’s who of integral personalities including key Nation of Islam members, Ali’s first Louisville backers, Ali’s first wife, brother, daughter, and many more who add a credible weight to the film.

There are real shocks, too. Some of the footage shows the mature Ali becoming a product of his environment, speaking from a dangerously racist, separatist viewpoint – everything the young Ali despised. In an interview in 1968, the late Sir David Frost asks Ali: “You were quoted on one occasion as saying ‘all whites are devils.’ But that’s not true, is it?” We want to cheer when Ali’s reply – “Elijah Muhammad teaches us that God told him that all whites are devils” – is smartly knocked back by Frost: “Well, God was wrong on that occasion, wasn’t he?”

In another interview scene from the same year, British chat show host William F. Buckley, suggests to Ali that Elijah Muhammad “is poisoning your mind.” The film shows with unflinching honesty the unsavoury choices Ali made during those years. Our understanding as an audience of the complex racial tensions of the time does little to ease the discomfort.

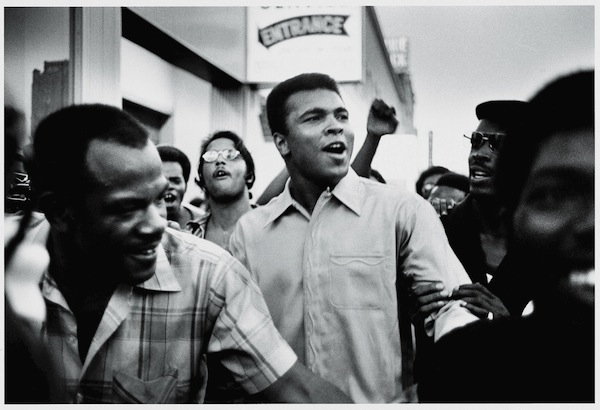

Muhammad Ali walks through the streets of New York City with members of the Black Panther Party in September 1970. Credit: David Fenton/Archive Photos/Getty Images

From the thick of these divisive events in it’s easy to forget that Muhammad Ali managed to progress from enemy of the state to become one of the most loved and enduring role models of the 20th century. How were the appalling views mitigated? How was his reputation salvaged?

The answer is sheer, balls-out bravery. The answer is one man risking everything to say no to a government that didn’t give a second thought about sending hundreds of thousands of its sons off to die in an unnecessary war; one man prepared to get in the way, whatever the cost. The Trials of Ali doesn’t merely dote on the glamour of Ali’s footwork in the ring; it shows us the strength of character and determination of a man who fought for justice over ‘the system’. Ali might have got very, very lost, but this film still manages to remind us that you can both be true to yourself and still win the fight; even when your fists are down.

Words: Vernon Ward