PHOENIX’s assistant editor Mary-Jane Wiltsher gets a glimpse of acclaimed artist Hormazd Narielwalla’s cutting-strewn world to talk cubism, anatomy in art, and childhood memories of India…

Crafting our GODS & MONSTERS issue spurred questions of mortality, physicality and ‘grand designs’, so it seems only right to get acquainted with an artist whose work is imbued with a sense of these subjects.

Hormazd Narielwalla is a master of creative resurrection, transforming the bespoke tailoring patterns of deceased Savile Row customers into anthropomorphic collages and 3D skull sculptures. Using electric colour and precise composition, he reinvents a discarded means of production, giving it new life.

Originally trained in menswear design, Narielwalla began his career at the Savile Row tailoring firm Dege & Skinner, where he discovered a collection of old patterns destined for the shredder. Unsettled by the idea of them being destroyed, he asked if he might keep them. It was the first step on a journey that led him to win the Saatchi Art Showdown prize for his work Le Petit Echo de la Mode No.5 earlier this year. Along the way, he’s published an artist’s book, Dead Man’s Patterns (2008), penned The Savile Row Cutter (2011) – a biography of tailor Michael Skinner – produced a solo show with Paul Smith, and exhibited at the exclusive Saatchi Suite.

First of all, congratulations on winning Saatchi Art’s Showdown prize for ‘Le Petit Echo de la Mode No.5’ earlier this year, how did it feel?

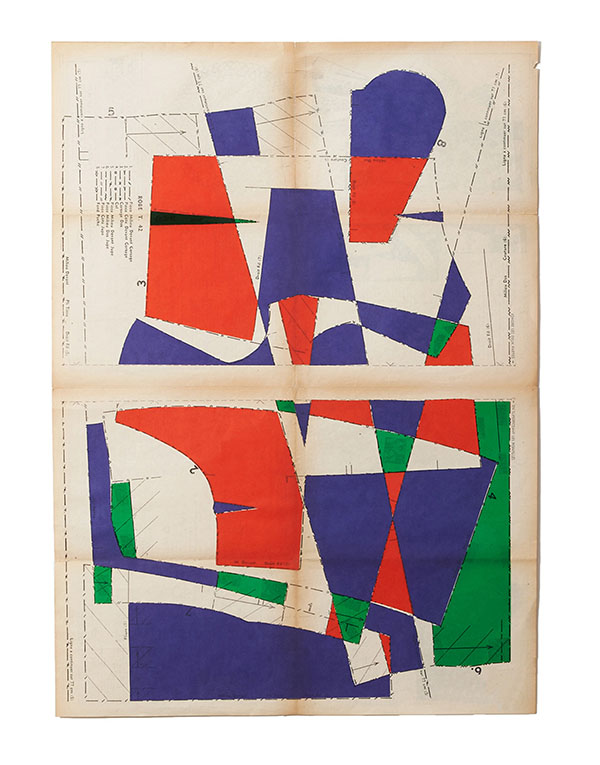

I was thrilled. The competition was ‘The Body Electric’, encouraging artists to submit work that depicted the body. Le Petit Echo de la Mode translated into English means ‘the little voice of fashion’. The work was created from an antique French domestic tailoring pattern. The patterns for an entire garment are laid on top of each other – it shatters the female form into precise overlapping facets. Predating Futurism and prefiguring Cubism, the artworks made from these patterns have abstracted the female subject to a degree more radical than the highest aspirations of the 1912 manifesto ‘Du Cubisme’.

Where do you create your work?

My studio in Bow is my haven, with hundreds of tailoring patterns hanging from the walls, or suspended from the ceiling. At the moment my floor is covered in detritus after several days of work.

Describe your first memory of art?

Visiting the Elephanta caves in Mumbai as a young boy. I also found catalogues of the old masters like Rembrandt, Goya, Constable and more in a paper shop – a place where old magazines, newspapers, and catalogues are brought from all over the world. If they fail to sell, they’re turned into pulp.

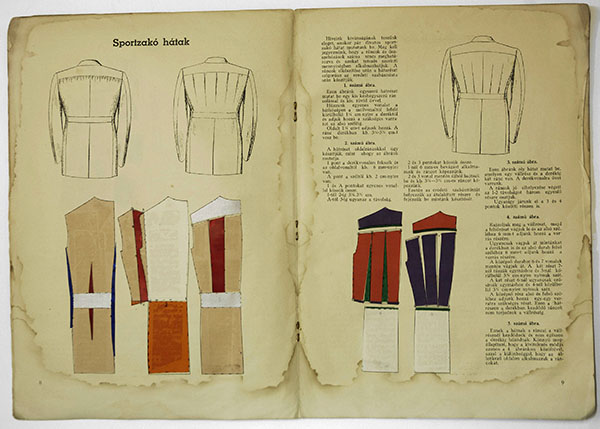

Cuttings in Narielwalla’s Bow studio

Tell us about your time at Savile Row’s Dege & Skinner, and the moment you first discovered the discarded tailoring patterns?

I initially trained in fashion, specialising in menswear. While taking my Masters I met William Skinner, the Managing Director of Dege & Skinner. I discovered that the bespoke tailoring patterns of customers now deceased were going to be shredded – a thought that made me melancholic. I wanted to resurrect them in some way and make beautiful timeless objects out of them.

Why do you think there is such curiosity attached to anatomical materials?

The patterns are incredibly graphic and beautiful compositions in their own right. Their history, their story, and the fact that they are templates of us humans make these patterns an interesting source material. I’m taking these abstractions and bringing them into a contemporary context.

What was your thought process while transforming the patterns?

There was no point in making a suit, as the body no longer existed. I began to view them as abstracted shapes of humans, as they not only carry with them an outline of the body, but also an impression of the body. I started playing with them to create 2D and 3D works. My 3D skull sculptures suggest the very nature of the patterns’ existence. When I realised how many records of deceased customers had been preserved, I wanted to capture that feeling by creating something raw and representational of death. Just like the bespoke suits, each skull is unique in its details.

‘Le Petit Echo de la Mode No.5’

Fashion is cyclical by nature, but its less common to upcycle a means of production, does that account for this art form’s appeal?

As a youngster growing up in India, precious commodities usually had the tag ‘Made in England’. Now this is a rarity, and especially relevant for the existence of Savile Row. Once there were more than 300 tailoring houses making suits, but mass production means this number has reduced to a handful. My work offers a window that allows a new audience to appreciate the process of making clothing.

What’s next for you?

I’m working on a book project titled Anani Tales, a limited edition artist’s book launching next year, and am also adding work to my Le Petit Echo de la Mode series. I’ve recently been awarded my PhD, so a little break is in order for me to reflect and plan for the coming years!

‘Seducing Matisse’

From ‘Hungarian Peacocks’

Imagery: Denis Laner