The psychotropic brew used by the indigenous peoples of the Amazon can heal mental, and in some cases terminal, illness… as long as you’re prepared to take a long, hard trip

The first time I drank ayahuasca I saw God, the second time I saw monsters.

Let me explain. It’s a typically hectic Friday night in Brixton, people spill out of the tube onto the street and head for the nearest bar, searching for oblivion.

A block back from the main drag and I’m searching for the opposite – clarity through La Medicinia, The Vine of the Soul, Mother Ayahuasca. There are many names for the psychoactive medicine used by the indigenous peoples of the Amazon for thousands of years. Beat author William S Burroughs wrote to Ginsberg in The Yage Letters about his quest for the tea to cure him of his opiate addiction.

My twenties took their emotional toll, a catalogue of failed relationships, dramatic career shifts and being transplanted to the capital. It’s surprisingly easy to be lonely when surrounded by 8million people. Dark, tempestuous feelings clouded my brain, one near miss with a nervous breakdown and a brief foray into the twisted world of eating disorders and I knew I needed change. I had already tried various traditional therapies, daily yoga practice, meditation and exercise, but nothing seemed to lift me fully out of the gloom. Anecdotal reports likened ayahuasca to the equivalent of 10 years therapy in one night. Which is how I came to find myself in a south London basement with 20 strangers and three shamans, clutching a plastic bucket from Poundland.

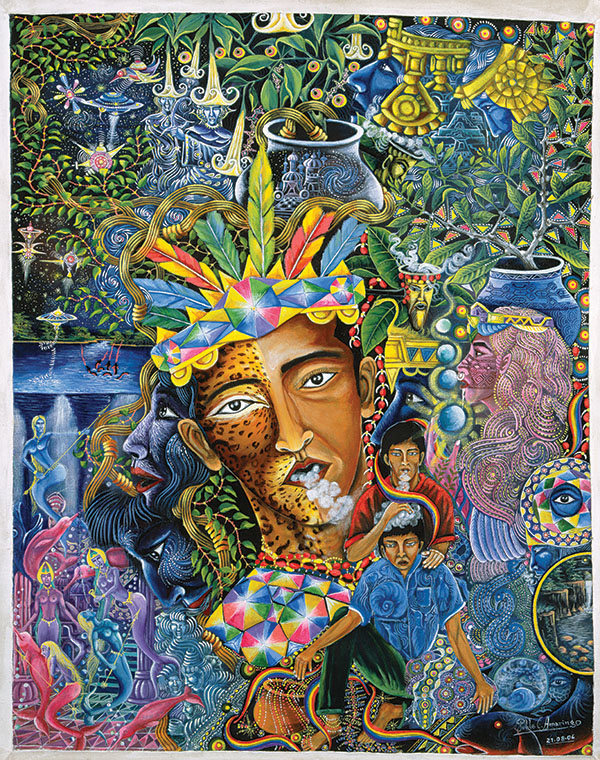

Painting: Pablo Amaringo

The head shaman is a tiny, raven-haired girl called Nejra. “I may look young but I’ve been holding ceremonies for 14 years”, she says in a thick cockney accent, “It cured my drug addiction.” She married a Peruvian shaman and lived with him in the jungle for almost a decade.

Eminent doctor Gabor Mate considers that many of the ailments afflicting modern-day man, such as cancer, addiciton and depression are adaptations to stress and trauma. In his speech at the Psychedelic Science 2013 conference he proposed, “what if we actually got that human beings are bio-psycho-spiritual creatures by nature—which is to say that our biology is inseparable from our psychological emotional and spiritual existence?” Brazilian scientist Eduardo E. Schenberg agrees the hallucinogenic brew is worthy of further study as a potential alternative cancer treatment after 7/9 of his test patients showed marked improvements.

The psychoactive tea is made from the jungle vine Banisteriopsis caapi and the leaf Psychotria viridi. The primary drug involved is N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a natural substance that can be found within the bodies of all mammals, and one of the most powerful hallucinogens known.

Normally DMT is broken down in the digestive tract and doesn’t reach the brain, however a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) in the vine allows it to circulate freely for around five hours. How the indigenous peoples of the Amazon discovered these synergistic properties is unknown, they claim they were told by the plant spirits themselves. DMT is considered a class A drug, it was made illegal as a manufactured hallucinogen before it was known it existed in natural form in the plants used to make ayahuasca. Only one man has gone to prison for administering it in the UK, and in 2012 a second case was dropped by the Home Office. Studies show it is non-addictive, non-toxic, and in its classical forms, produces no physical or psychological harm to the users.

“We call her Mother Ayahuasca,” says Nejra*, “because mothers can be gentle and loving, but also they know what’s best for you and, if you need it, they’ll give you a good ticking off! She won’t show you anything you’re not ready or capable of dealing with. If you go to a dark place, remember that we need to relive pain from our past in order to deal with it and fully let go. You have to step up with a warrior spirit: Mother Ayahuasca will do some of the work, but you have to be prepared to do your 50%.” I’m getting nervous, I look at the door but it’s too late now. Nejra’s final words: “remember, we are all her children and she loves us very much. I bless your journey.”

The room is lit with candlelight. “Knock it back like tequila” we’re told. The thick, dark liquid tastes like a combination of forest floor and cough syrup, I find it surprisingly sweet. I go and take a seat back on my sleeping bag. We’re told to try and keep it down for 45 minutes. I can feel the liquid burning its course down through my gut. The shamans chant icaros, hauntingly songs of the spirits. “If ayahuasca is the ship, the icaros are the oars to guide you when you start to feel lost,” says Emma the apprentice shaman. There’s the clicking and whirring of chacapas, leaf fans that sound like birds of paradise. The temperature in the room has climbed over 10 degrees and the air becomes inexplicably clouded. I shut my eyes and kaleidoscopic rainbows explode across my brain, expanding then collapsing upon themselves into a million neon fractals. The visual geometry is a common theme to the ayahuasca experience, and it’s reflected in the beaded jewellery and ceramics of the native Shipibo people of Peru. I look down at my arms and they melt into transparency, I realise that I’m looking at myself at a cellular level; and as I pan my gaze across the room, in the darkness I see the others as glowing bundles of cells and pure energy. I feel an overwhelming sense of oneness and euphoria.

Not everyone is as lucky, I can see a tall man called Robert rocking violently in a foetal position, one of the girls I met earlier is howling like a wild animal. The shamans move between them, helping when the spiritual shadow-boxing becomes too much to take. Childhood memories are floating round the carousel of my consciousness. The word “cheerful” reappears again and again in my mind. I feel certain Mother Ayahuasca is trying to remove self-imposed shackles of depression. Purging is a well-documented part of the cleansing process, and I feel relief from vomiting. Others were helped towards so the bathrooms.

The ceremony calls upon several jungle medicines in conjunction with the ayahuasca: sananga, eye drops that cause an intense burning like hot chillis but leave you clear-headed and your eyesight sharp. The third shaman Luke, an attractive wild-maned man in his mid-twenties blows rapé, a kind of snuff made from herbs, pollen, and jungle tabacco through a pipe up my nose. It’s like a bullet in the brain, firing all the neurons simultaneously. Apparently it aligns your chakras. As the medicines wears off we sit in a circle in the dark and join the shaman in song. “Collective singing and praying is very tribal,” explains Nejra. “It’s a powerful tool in spirituality.” As part of the closing ceremony we are invited to share our experiences. My fellow night-trippers have come to deal with a wide array of issues, from childhood rape, to suicidal thoughts, and the grief of losing a child. My so-called problems pale in significance. They describe their experiences using adjectives such as “magical”, “life-changing”, and “profound”. Weeks after the ceremony I’m still feeling the positive effects, years of self-destructive behaviour seem cured overnight and I float around like I’ve discovered the key to the mysteries of the universe.

I don’t plan to drink again so soon, but a close friend asks me to take her. Normally in the fortnight before you drink you are instructed to follow a strict dieta: no gluten, no dairy, no caffeine, no alcohol, no drugs, no sex, no red meat. You are instructed to rest and spend solitary time immersed in nature. This time I’ve been working 16 hour days on deadlines and mainlining caffeine. Even as I step up to drink, I know that something was different. The liquid now tastes intensely bitter and I gag, forcing myself to keep the medicine down. When it takes hold my body reacts in spasms, as though electrical currents are crackling through my nerves. An intense twisting pain in my abdomen bends me double for four hours.

I feel a great feline spirit take possession of my body, a jaguar. My eyesight became crystal-clear in the darkness, and the sound of subterranean trains passing changed from a rumble to a roar. Demons crowd at the edge of my peripheral vision. I’m shown movie clips of painful arguments with my mum, and made to feel empathy for her side of the story. I feel shame for how I’ve treated her. I touch my cheeks and find hot, wet tears streaming down. I clutch desperately at my bucket and vomit… despite having fasted for a day a tar-like, black substance comes up. By the time the dawn comes I feel like I’ve journeyed to the underworld and back. Surprisingly though, I feel completely energised and calm. Any latent anxieties have disappeared, and I feel that any residual negativity has been purged. My rational brain tells me that even though the DMT can explain the hallucinations, such a simplistic view of the experience falls apart.

As Schenberg writes, “If ayahuasca is scientifically proven to have the healing potentials long recorded by anthropologists, explorers, and ethnobotanists, outlawing ayahuasca or its medical use and denying people adequate access to its curative effects could be perceived as an infringement on human rights, a serious issue that demands careful and thorough discussion.”

When the time calls for it, I will be ready for another journey to the spirit realm.

*Names have been changed to protect the identity of the shamans.

Words: Skyler Thompson