★★★★☆

Hannah Höch, Whitechapel Gallery, until 23 March

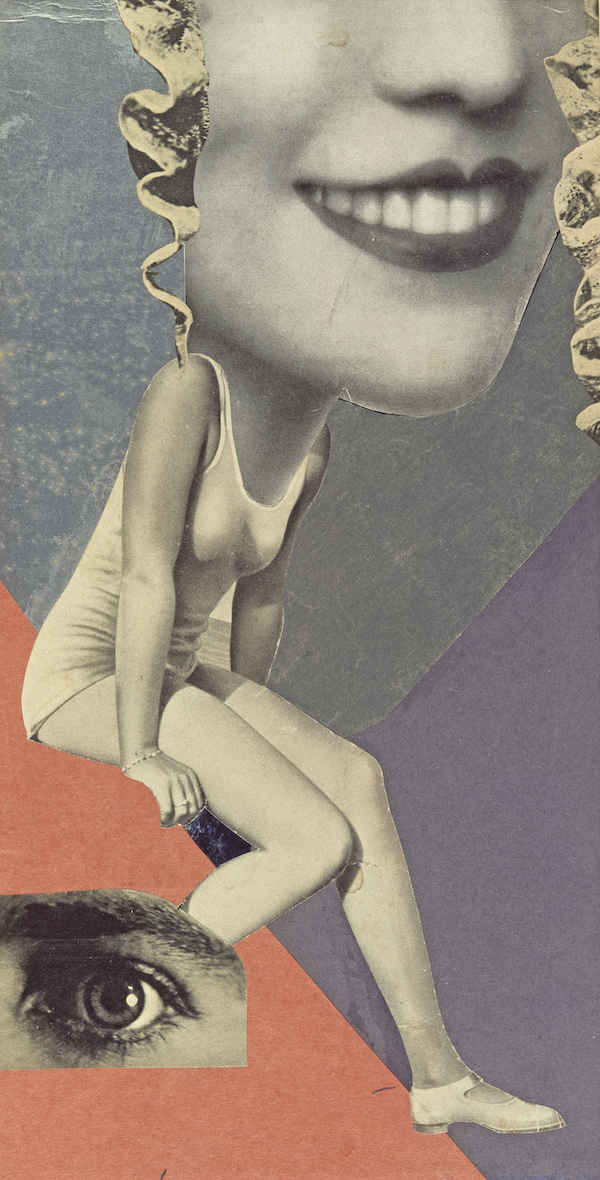

Für ein Fest gemacht (Made for a Party), 1936; Photomontage 36×19.8cm; Collection of IFA, Stuttgart

It’s about time Brits got better acquainted with the wonderful, witty art of Hannah Höch. A dazzling pioneer in collage and photomontage during the early years of the twentieth century, Höch has nevertheless been almost totally excluded from both the Berlin Dada group to which her work belongs, and art history in general, presumably because of her gender. Thankfully, the authoritative and attentive exhibition currently running at the Whitechapel Gallery – the artist’s first major exhibition in the UK – is a reassuring sign that her work is starting to gather the appreciation it deserves.

Those expecting an array of prettily arranged paper cuttings will be shocked, although not disappointed, as the works displayed are intricately narrative and ruthlessly political, offering a vital insight into Weimar Germany and the social milieu in which Höch lived. Initially coined by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, the term ‘collage’ points towards a medium simultaneously serious and tongue-in-cheek; a technique that is deeply referential of the political world in which the works were produced. Via the assemblage of different images, collage interrogates the fundamental concept of what it is to create art, whilst offering a prismatic reflection of the social upheaval of the twentieth century. The exhibition chronicles Höch’s work before and after the Second World War across two separate floors, documenting her development of collage through her visually dynamic hybrids.

Born in 1889 in Thuringia, Höch escaped her parents’ desire to see her married and at 22 enrolled at the school of applied arts in Berlin, where the study of textile crafts was deemed suitable work for a woman. On leaving school, she worked for the publishers Ullstein, completing the embroidery patterns which make up the first section of the exhibition. Early sketches on display show beautifully drafted female nudes, whilst the patterns themselves hint at the eclectic and rhythmically taut colours and shapes of her later collages.

The Berlin Dada manifesto of 1918 called for a “simultaneous muddle of noises, colours and spiritual rhythms,” but Höch’s work is far from muddled. The works of the turbulent Dada period are elaborately arranged in tight patterns; each work on paper is much smaller than one might expect. Her politics are realised initially through humour, but on deeper inspection the jokes are, in fact, dangerously critical. Höch also employed the new technique of photomontage, splicing older images together to activate them in new ways.

Ohne Titel, aus der Serie: aus einem ethnographischen Museum (Untitled, from the series: From an Ethnographic Museum), 1929; Photomontage with collage; 49×32.5cm; Federal Republic of Germany – Collection of Contemporary Art; Image: bpk / Kupferstichkabinett, SMB / Jörg P. Anders

In the politically satirical “Heads of State” (1918), the artist pastes paunchy images of Weimar’s President Friedrich Ebert and its Minister of Defence Gustav Noske in their bathing suits against a childish background of a whimsical beach scene; in “The Father” (1920), she subverts the conventional family nucleus with a photograph of a middle-aged man, on top of a female body, cradling a baby which is being punched by a boxer. The background offers a mesh of svelte, prancing female figures, drawn from women’s fashion magazines and advertisements.

The works perhaps reflect her own unconventional lifestyle. Höch had an affair with fellow artist Raoul Haussmann, before her relationship with Dutch female writer Til Brugman. She married and divorced the German businessman, Heinz Kurt Matthies, but proceeded to live by herself. Through her images, Höch attempted to reveal the warp of Weimar society itself, the sidelined position of women and the promotion of the increasingly Aryan family against the backdrop of emerging fascism. Most irreverent and disturbing are the images “Flight” (1931), in which the central figure has the head of an ape, and “The Peasant Couple” (1931), in which one ape-headed female figure stands alongside the face of a black man wearing a colonial hat. These are difficult images to read, but when considered against the growing presence of fascism and ideals of racial and ethnic purity in Höch’s homeland, they begin to make shocking sense.

“I would like to blur the firm borders that we human beings are, are inclined to erect around everything that is accessible to us… I want to show that small can be large, and large small, it is just the standpoint from which we judge that changes… I also want to show that there are millions and millions of other justifiable points of view besides yours and mine. Today I would portray the world from an ant’s-eye view and tomorrow, as the moon sees it, perhaps, and then as many other creatures may see it,” wrote Höch in the catalogue to her first exhibition opening in The Hague in 1929. The quotation aptly describes the unique perspectives offered in Höch’s works, and the charm which can often be found alongside the more disturbing tones. Höch plays with minute images and negative spaces, encouraging the viewer to appraise the images in relief; figures in profile, missing eyes juxtaposed against her trademark larger, single eye and silhouettes all play a part in a narrative in which criticism and humour is deeply implicit.

Flucht (Flight), 1931; Photomontage 23×18.4cm; Collection of IFA, Stuttgart

Upstairs, we encounter Höch’s post-World War Two work including her beautifully constructed “Album” of 1934. Never intended for exhibition, “Album” is a scrapbook containing whole images collated together, offering an insight into German magazines of the time and the idea of the ‘New Woman’ (sporty, fashionable, capable) being promoted after the war. Until 1945, Höch had lived in quiet seclusion in a cottage on the outskirts of Berlin where she had grown flowers – she recognized her garden as a kind of therapy – and collected trinkets. After the Allied troops liberated Germany, she began to exhibit again. Her diary entries of the time record a superseding sense of calm, reflected in her work. In “Dove of Peace” (1945), a single bird sails airborne through harsh metal structures, which are receding into the distance. Elsewhere, the works are dreamy, with exotic females and floating shapes. They are non-narrative and increasingly abstract; Höch herself called them “fantastic”. They have lost the tautness of the pre-war material; no longer tense with political meaning, they are, perhaps, less interesting for it, though the gallery must be applauded for documenting the trajectory of Höch’s career as a whole.

The exhibition closes with Höch’s glorious “Life Portrait” (1972 – 72) – the last work she completed before her death in 1978: a vast collage of portraits of the artist throughout her life. With characteristically playful perspectives, the artist herself is finally illuminated. It is a fitting end to an astounding body of work – brilliantly humorous, critical and disarmingly charming.

Words: Harriet Baker