Julie Reid ‘meets’ the man who changed art forever

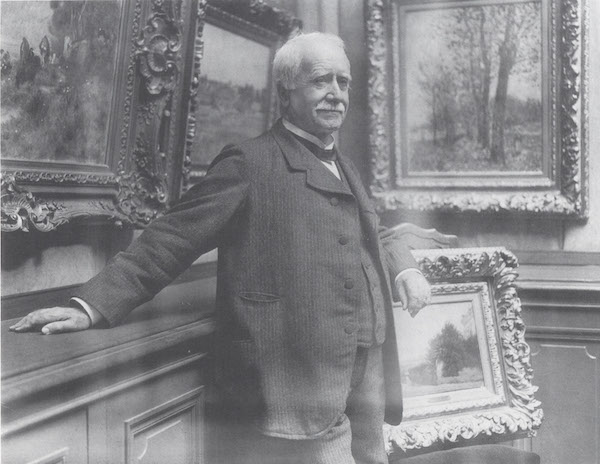

Photograph of Paul Durand-Ruel in his gallery, taken by Dornac, about 1910 © Archives Durand-Ruel © Durand-Ruel & Cie

In some respects Impressionism has become something of a cliché, with its ubiquitous Monet umbrellas, Renoir tote bags, Degas greeting cards and the like. But what many may not know is that in its early days it was a rebellious movement and the artists were labelled subversive, provocative and even inflammatory. They were out to upend the status quo, not play by the rules.

This early period is the subject of the National Gallery’s exquisite 85-piece exhibition Inventing Impressionism: The man who sold a thousand Monets, open through 31 May. The man in question is entrepreneurial art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel whose faith, tenacity and innovative business strategies kept the nascent movement afloat. It’s an exhibition that provides context, which leads, in turn, to a greater appreciation of the works of art.

The rooms are arranged chronologically, following the story of Durand-Ruel. He was born into a family business of art dealers and first realised the beauty of contemporary art through Barbizon artists such as Delacroix, Rousseau and Millet (the ‘beautiful school of 1830’). Durand-Ruel played an integral role in rescuing Rousseau from financial ruin and through the experience had a moment of epiphany. He described it as a “triumph of modern art over academic art that permanently opened my eyes. I could be of service to true artists, helping them be better understood and appreciated”. He’d found his calling as the patron saint and champion of the underdogs.

The Mill on the Couleuvre near Pontoise, Paul Cézanne, about 1881 © Photo Scala, Florence / bpk, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin / Photo: Klaus Goeken

During the Franco-Prussian War, Durand-Ruel moved his business and family to London, where he first met Monet and Pissarro and began to exhibit their works. Back in Paris the following year, he was introduced to Manet and immediately purchased 23 of his works in one go. This shrewd move of bulk-buying as many works as he could, which he was to repeat over and over with the assistance of bank loans, meant he held control of the stock and could influence demand and prices. He set out to prove to the world that Impressionism was serious art, worthy of collecting.

It was, to put it mildly, a struggle. The Paris Salon kept its doors firmly shut against the interplay of light and shadows, the chance movements and awkward arrangements that were presented. The critics sneered at the subject matter dealing with simple nature scenes and the daily life of the working-class. And audiences, most of whom were confounded by the swift brushstrokes and unfinished canvases still showing primed surfaces, simply laughed.

Durand-Ruel persisted. Over the course of 30 years, he was a driving force behind the men and women of Impressionism. The central storyline is the way he modernised the art industry. By creating comfortable exhibition spaces, even opening his own apartment to show that these avant-garde pieces could work within a respectable and stylish French home, he made the art accessible to the public.

He held evening lectures, provided a catalogue of etchings for press, started a monthly art magazine, organised solo shows and retrospectives and opened up the international art market where the work found a more willing reception. He even went so far as to offer a money-back guarantee, promising to buy back the artworks if clients decided they weren’t ready for the modern age just yet. Beyond his role as art dealer, he opened his home to them as family members, provided financial stability in various ways and was unfailing in his belief and encouragement.

Woman at Her Toilette, Berthe Morisot, 1875-80 © The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois

It’s a wonderful character study of a complex man, but the true stars of the show are the paintings. As you walk through the rooms, you encounter masterpiece after masterpiece – fresh, immediate, dynamic. It was as though you’ve stepped into an art history textbook – they’re all here. Renoir’s Dance in the Country, Dance in the City and Dance at Bougival. Monet’s garden scenes, The Galettes and five of his Poplars canvases. Berthe Morisot’s Woman at her Toilette and Mary Cassatt’s The Child’s Bath. Cezanne, Pissarro, Manet – the list goes on and on. I could have stayed for hours.

The exhibition deserves all the praise that has been lavished upon it. Go for the paintings by all means, but you’ll also be intrigued by the story of Durand-Ruel. In Inventing Impressionism, the National Gallery gives us an exhibit full of depth, drama and the human experience. It is engaging and affirming, a story of David triumphing over Goliath that continues to inspire.

Open until 31 May at the National Gallery London. Visit here for tickets and more information.

Words: Julie Reid