Julie Reid finds Marlene Dumas light on hope, heavy on beauty

Marlene Dumas, The Image as Burden 1993 © Marlene Dumas. Photo: Peter Cox

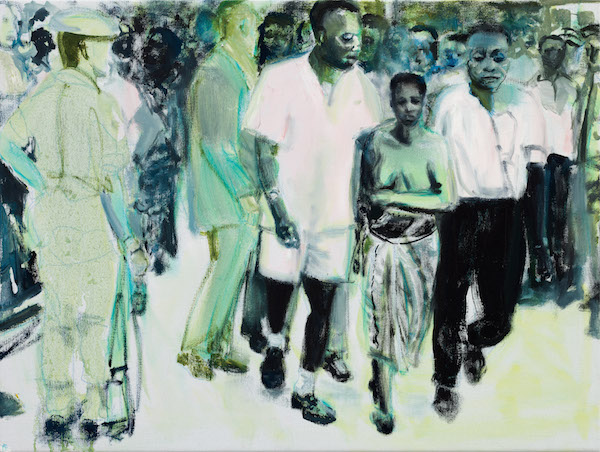

Once labeled ‘the world’s most interesting figure painter’, Marlene Dumas (b.1953) is famous (although not quite as famous as she should be) for intense, psychological, emotionally-charged works which use the human form to embody such diverse topics as politics, sex and grief.

The variety and scale of her output is revealed in Marlene Dumas: The Image as Burden, a huge retrospective of her work that has just opened at Tate Modern, filling 14 rooms with over 100 of her most iconic paintings and drawings. It’s safe to say that her reputation – already glowing in the art industry – is about to take its place firmly in the mainstream.

Believing that ‘secondhand images can generate first-hand emotions,’ Dumas uses photography as her source material; either photographs she or her friends have taken, or those she has seen in the news. As the introductory text in room four puts it, in a quote of hers from 1985:

‘My people were all shot

by a camera, framed

before I painted them.

They didn’t know that I’d do this to them.

They didn’t know by what names I’d call them…

My best works are erotic displays

of mental confusions

(with intrusions of irrelevant information).’

Dumas draws heavily on art history, culture and current events in her work as well as her childhood memories of growing up in South Africa under apartheid. Her figures and portraiture transcend the sitter, asking broader questions about society and politics. The exhibit provides a stark commentary on humanity’s varied forms – and if you’re looking for hope or optimism about the future, you’ll have to squint.

Marlene Dumas, Evil is Banal 1984 © Marlene Dumas. Photo: Peter Cox

In the aforementioned room four, we encounter the self-portrait Evil is Banal 1984; we are warned, by its titular reference to Hannah Arendt’s writings on the trial of a Nazi officer involved in the Holocaust, of our inherent capacity to commit atrocities against our fellow man.

Room 11, thematically summarised by the phrase ‘art is a way of sleeping with the enemy’, contains her controversial paintings of a gentle-looking Osama bin Ladin, Mohammed Bouyeri (who killed Theo Van Gogh) and a group of men praying against the West Bank Barrier that divides Israel from Palestine. Room 12 explores the very thin line between pornography and eroticism; the final rooms grief and death.

Be warned: this is not an easy ride. You need plenty of time to absorb the big and complex emotions in Dumas’s work, and you’ll feel exhausted half way through.

But the art is undoubtedly moving – technically virtuoso, viscerally felt- and there are moments of joy and triumph. One such moment is Great Men 2014, a series of works on paper celebrating notable homosexual men over the past two hundred years. This collection was created in response to Russia’s stance against homosexuality and exhibited boldly in that country last year.

Another is the playful Don’t Talk to Strangers 1977, in which Dumas tears out the beginnings and endings of personal letters and connects them at either side of a large canvas by beige lines; the redacted contents both intriguing and resisting our onlooking eyes.

Marlene Dumas, The Widow 2013, © Marlene Dumas

Vague titles on works of art can frustrate me; I end up feeling lost in an expanse of limitless interpretation. But Dumas uses titles and subtitles strategically. Moving through these rooms, I felt as though she was guiding and refining my understanding of what I was witnessing. She started the thought, then left me to finish it, to find what was meaningful to me and my experiences.

What then are we to make of the exhibit as a whole, titled significantly The Image as Burden? The curators say that ‘Dumas draws a connection between the subject of the painting, and the painter who carries the weight of her subject. Her interest lies in the impact that the act of painting has on the image, rather than that of the image on the painting.’

But the physical body, the subject matter of these 100-plus images, is in itself a burden. Our physical representations stir up complex emotions about race, gender, class and values. These emotions, left unchecked, can block us from seeing a shared humanity in each other and lead to the atrocities she referenced above. By opening our eyes to this, perhaps we can learn to see something deeper that connects us all.

This is a gripping exhibit, but not one that is easily accessible. Dumas makes you work for the payoff. But it is there in the end if you persist.

Marlene Dumas: The Image as Burden is on at Tate Modern until 10 May.

Words: Julie Reid