Think the Women’s Prize for Fiction is outdated? Think again, says Books Editor Sarah Shaffi

Words Sarah Shaffi

“Are you sure we need a prize that’s just for women?” “Isn’t that a bit… sexist?” “If the work was good enough, it wouldn’t need a separate award.”

Every year, without fail, the above comments do the rounds when the Women’s Prize for Fiction announces its longlist. And then when it announces its shortlist. And again when it announces its winner. (Similar discussions as to whether we still need a prize for, say, funny books, don’t take place around the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize.)

There are Twitter discussions, and segments on radio shows, and think pieces. I’m here to add to the latter – yes, we still need a book prize for women. And if you want to know why, read on.

Women buy the majority of books in the UK, yet men still write the majority of literary criticism. Each year VIDA – Women in Literary Arts – looks at who is being reviewed in 15 major literary publications, and who is doing the reviewing. Its latest statistics, for 2017, showed that just two publications – Granta and Poetry – published 50% or more women writers.

The remainder, including some of the biggest literary magazines in the world, failed to reach the 50% threshold. Some made a truly terrible showing – The New York Review of Books had women as just 24.7% of their contributors, while the London Review of Books had 26.9%.

But why does this matter? And why does it mean we need a book prize for women?

It matters because it creates a picture that serious literary criticism is for men. And with men doing the reviewing, it’s likely that the majority of books they’re talking about are also by men, meaning books by women are pushed out.

That confers an importance on books by men that isn’t given to books by women, and those attitudes can feed through into literary prizes, however unconsciously. The Man Booker Prize has been awarded to 31 men and 16 women in its history. The Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded to 114 individuals; of these, just 14 are women. Of the 65 Pulitzer Prizes in Fiction awarded since 1948, 18 have been given to women.

I’m not saying that the winners of these prizes aren’t excellent, but I am saying that it’s highly unlikely that women write far fewer good books than men do, or that their overall body of work is less deserving than men’s at a ratio of roughly 1:8.

“Arguments that worthy books will fight through crumble in a world where there is an inherent bias against books by women”

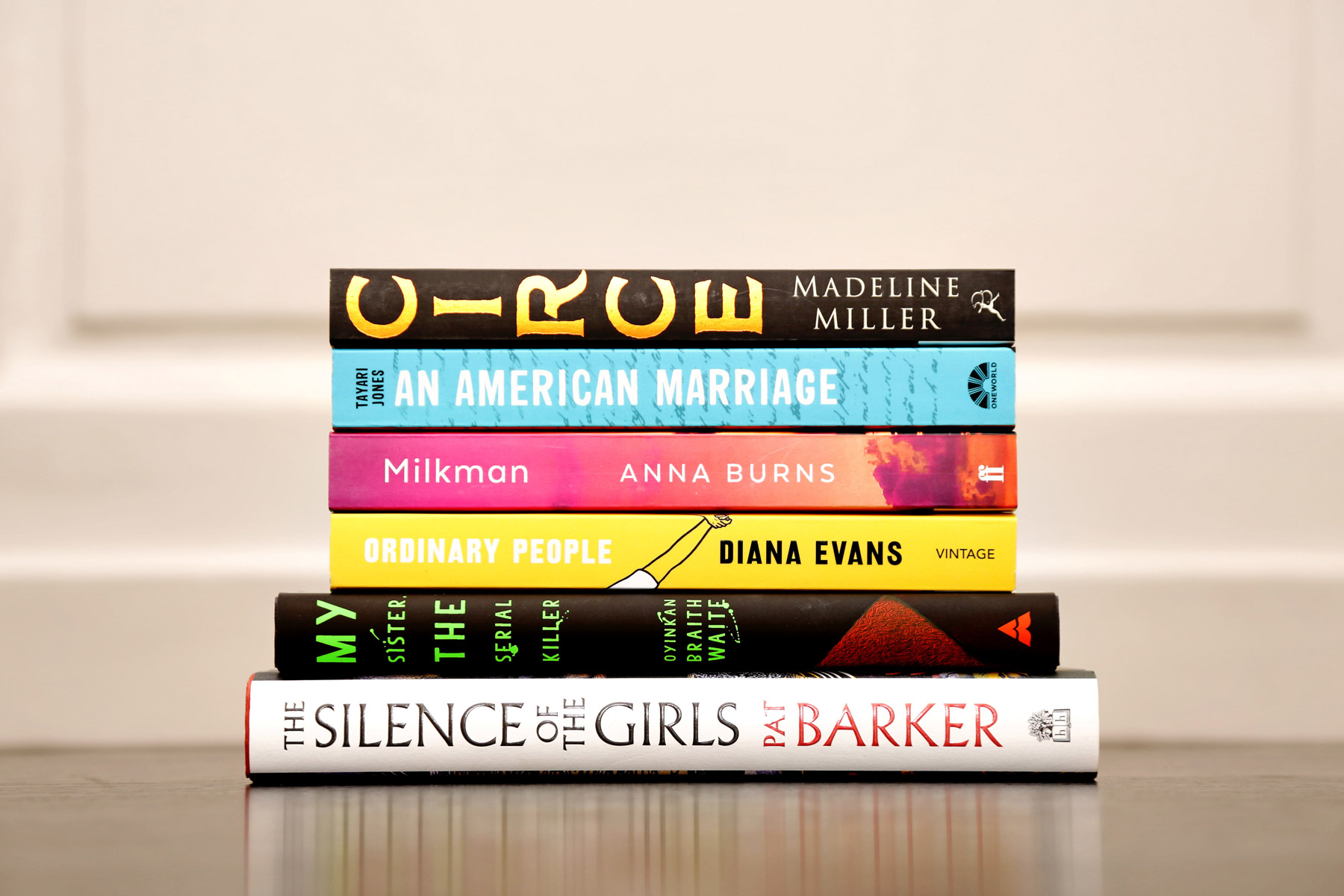

So there’s a clear imbalance that needs addressing, and to do that we need to shine a light on books by women. And that’s what the Women’s Prize for Fiction does.

The prize was set up in response to the 1991 Booker Prize, whose shortlist included no women. By 1992, only 10% of novelists shortlisted for the prize were women. The group behind the Women’s Prize decided that these statistics couldn’t be ignored, stating that “prizes are an influential way of bringing outstanding writers to the attention of readers”.

That’s the important thing about prizes – they bring books into public awareness. It’s not just about who won a prize in any given year, but also who was shortlisted and longlisted, who was in contention, and even, sometimes, who didn’t make the cut. All of that chatter around a prize highlights great books. Unfortunately, history has shown that with most prizes, that chatter is around books by men.

Arguments that the worthy books will fight through crumble in a world where there is an inherent bias against books by women, where books by women aren’t afforded as much time and space as books by men. Until they are, yes, we still need a prize just for women’s fiction.

SARAH SHAFFI

Books Editor

Sarah Shaffi is a freelance literary journalist and event chair, editor-at-large for the independent children’s publisher Little Tiger Group, and co-founder of BAME in Publishing.