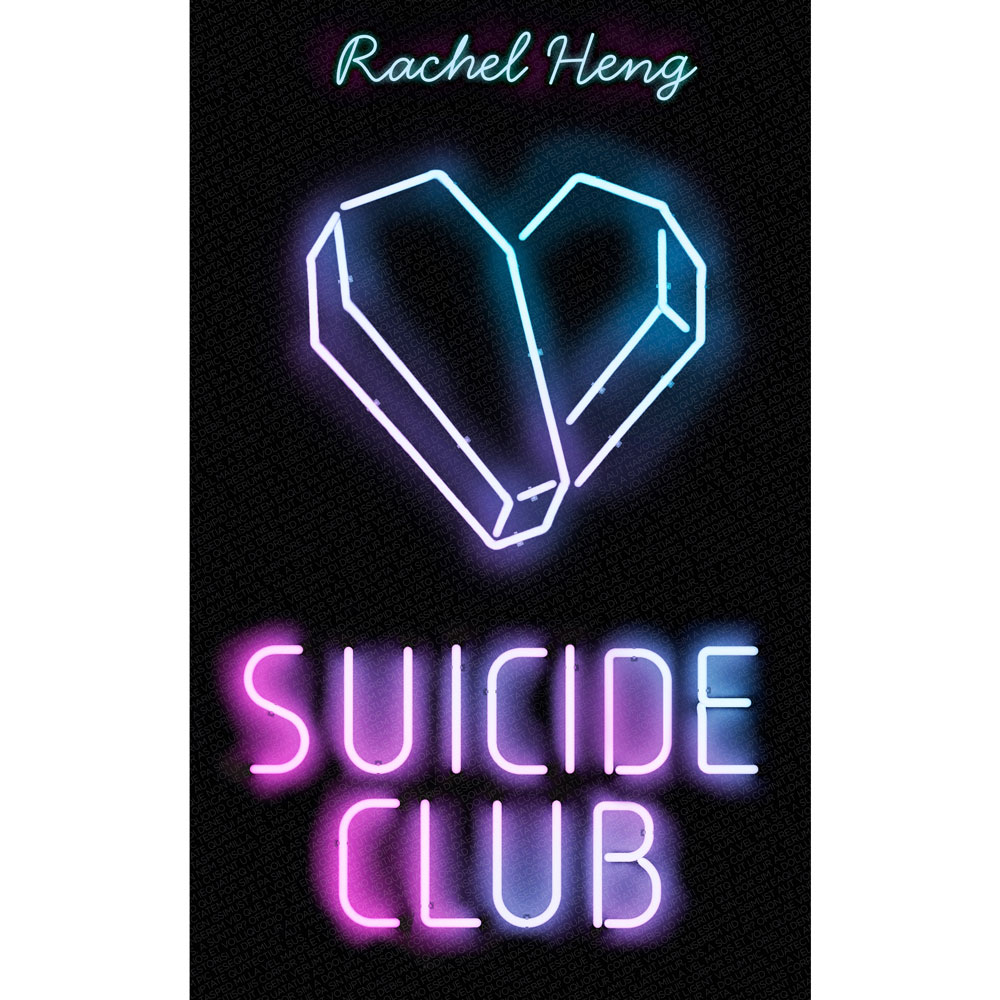

Would You Want to Live Forever? Rachel Heng Shakes Up Our Ideas About Death in New Novel Suicide Club

The debut author discusses immortality, inequality and the chilling pull of ‘wellness’

Words Sarah Shaffi

Death is, if I may be so bold as to say, having a cultural “moment”. We’ve always been fascinated with our mortality – it’s the one thing none of us can avoid – but the conversation about how we approach our own deaths seems to have recently ramped up.

At the start of this year, mortician Caitlin Doughty’s From Here to Eternity – a book in which she travelled the world investigating the way different cultures approach death – was released to acclaim. Then there’s Alua Arthur, a “death doula” who helps people plan for their own deaths and runs death meditation sessions, and who talks about her work in a video that has been doing the Facebook rounds. And following on from trends like lagom and hygge, there is now döstädning – Swedish death cleaning – which advocates removing unnecessary belongings and making your home nice in preparation for after you’ve gone.

One thing all of the above have in common is that they promote a “good death”. Which is surely a positive thing. But what if you wanted to avoid death altogether?

Imagine you could live forever. What would that look like? Would it be fulfilling and enriching – a chance for you to try out new experiences every day, travel the world, savour the best of life? Or would it be a chore? Would it involve sacrifice and discipline? And would immortality be available to everyone, or just to a select few?

These questions are explored to great effect in Rachel Heng’s debut novel Suicide Club – and I’m sorry to tell you that her vision of eternal life on earth is not one filled with fun and games. In fact, it’s a little bit terrifying.

The book follows Lea, who has a high-powered job, a successful relationship and is on track to be chosen as one of the lucky few who will get to live forever. But one day, on her way to work, Lea spots a man she thinks is her long-missing father and steps off the pavement. Her accident, although minor, gets her put on a monitoring list. Suddenly, her path to immortality is no longer guaranteed, and she attracts the attention of Suicide Club, an activist group which rejects the government’s strict edicts and indulges in everything that’s effectively banned, including death. As a contrast to Lea and her position of privilege, there is Anja, an immigrant whose mother is on the verge of death, but because of all the imperfect modifications to her body to help her live longer, can’t actually die.

Heng has been for years “mulling over” the idea of what would happen if people could live forever, but the book was finally prompted by an argument: “A co-worker asked why we could not legalise the trade of human organs. They said the poor villagers could sell their kidneys and [use the money to] send their kids to school. I could see where she was coming from, which was annoying. But we think if we create a market for everything and align it to people’s interests, it will work. I started thinking about the commoditisation of people’s lives, about health equality and lifestyle inequality.”

In the song ‘Wait For It’, from the musical Hamilton, the character of Alexander Burr sings: “Death doesn’t discriminate, between the sinners and the saints…” But in the world of Suicide Club, while death doesn’t discriminate, life certainly does. In the book, Lea hasn’t eaten sugar in years, and she exercises every day, but nothing too strenuous. In her world, health is a status symbol, and that’s an idea not a million miles away from the world we live in now, where “clean eating” bloggers advocate for diets devoid of sugar, gluten and dairy (and fun, in my opinion).

It is no longer cool to be dissolute and decadent and drinking alcohol. The new thing is to take care of your body and eat only vegetables, or a Paleo diet, for example.

“We live in this in environment of clean eating, of really expensive cold pressed juices and spin classes and whatnot,” says Heng. “I read a piece by Vogue about wellness as a new luxury status symbol, and it’s this notion that all of these trappings of wellness have become like the latest fashionable handbag. It is no longer cool to be dissolute and decadent and drinking alcohol. The new thing is to take care of your body and eat only vegetables, or a Paleo diet, for example. There’s this sense that wellness has become a status marker. So many of these things that are associated with wellness are often really expensive…a lot of it is that the high price point actually signals that this is an aspirational product. Some people could say that is harmless, but for me it is the image of virtue that goes along with that, the sense that taking care of yourself is linked with ideas of virtue, discipline and self restraint. It is all associated with rich people.”

The idea of wealth being the key to health, and health being a signifier of wealth, is taken to the extreme in Suicide Club – Hang says that she wanted to take things to a “ridiculous degree” and have fun – but again, it’s not far from reality. “There are billionaires in Silicon Valley trying to solve the pesky little problem of dying,” she says. “Alphabet has a lab where they’re trying to hack the signs of ageing. They see it as another kind of code. The only people who can live like this are billionaires. Even if a pill [to give eternal life] was invented, who’s going to get them?”

If Suicide Club is anything to go by, immortality is not desirable. “The average human being would see this would be a terrible existence,” says Heng. But has writing the book helped her come to terms with her own feelings, when she admits that she thinks about death “way more than is healthy”?

“I wrote this book as a kind of cautionary tale and thought experiment for myself,” Heng admits. “I don’t know about society […] but getting older and facing more deaths in the family is something I am coming to terms with.”

Rachel, we hear you.