Dr Clare Makepeace’s Captives of War reveals the human stories behind the myths

Words Greg Taylor

Most of our ideas of what life was like in prisoner of war camps during WW2 come from classic Easter Sunday movies. Favourites like The Colditz Story, The Great Escape and Escape to Victory celebrate stiff-upper-lip, never-say-die soldiers cocking a snook at buttoned-up Nazis while planning imaginative breakouts. They’re often thrilling and playful romps – exercises in tunnel vision underpinned by occasional glimpses of the real suffering and boredom that real-life POWs must have experienced.

Clare Makepeace’s Captives of War is very different. This extraordinary new book analyses for the first time the diaries, journals and letters of British POWs to expose the truth of how these everyday young men really dealt with captivity – their shock at being captured, their often strained relationships with fellow prisoners and the loved ones waiting for them, their individual coping mechanisms and internal psychological battles, and how they coped with freedom, often after years of devastating incarceration.

Makepeace, a young historian at the University of Birkbeck, has a very personal reason for delving into these hidden histories – her grandfather was held in Stalag XXB in Poland for most of the war. She movingly describes his conflicted thinking on his own experiences, revealing snippets of the horrors he faced to his family decades later, while lamenting his war-time personal history as one of humiliation that no-one could possibly be interested in. While Signalman Andrew Makepeace is no longer with us, his granddaughter has done him proud with a fascinating, compassionate and evocative exploration of the highs and lows of life in captivity, told directly and contemporaneously by the men experiencing it.

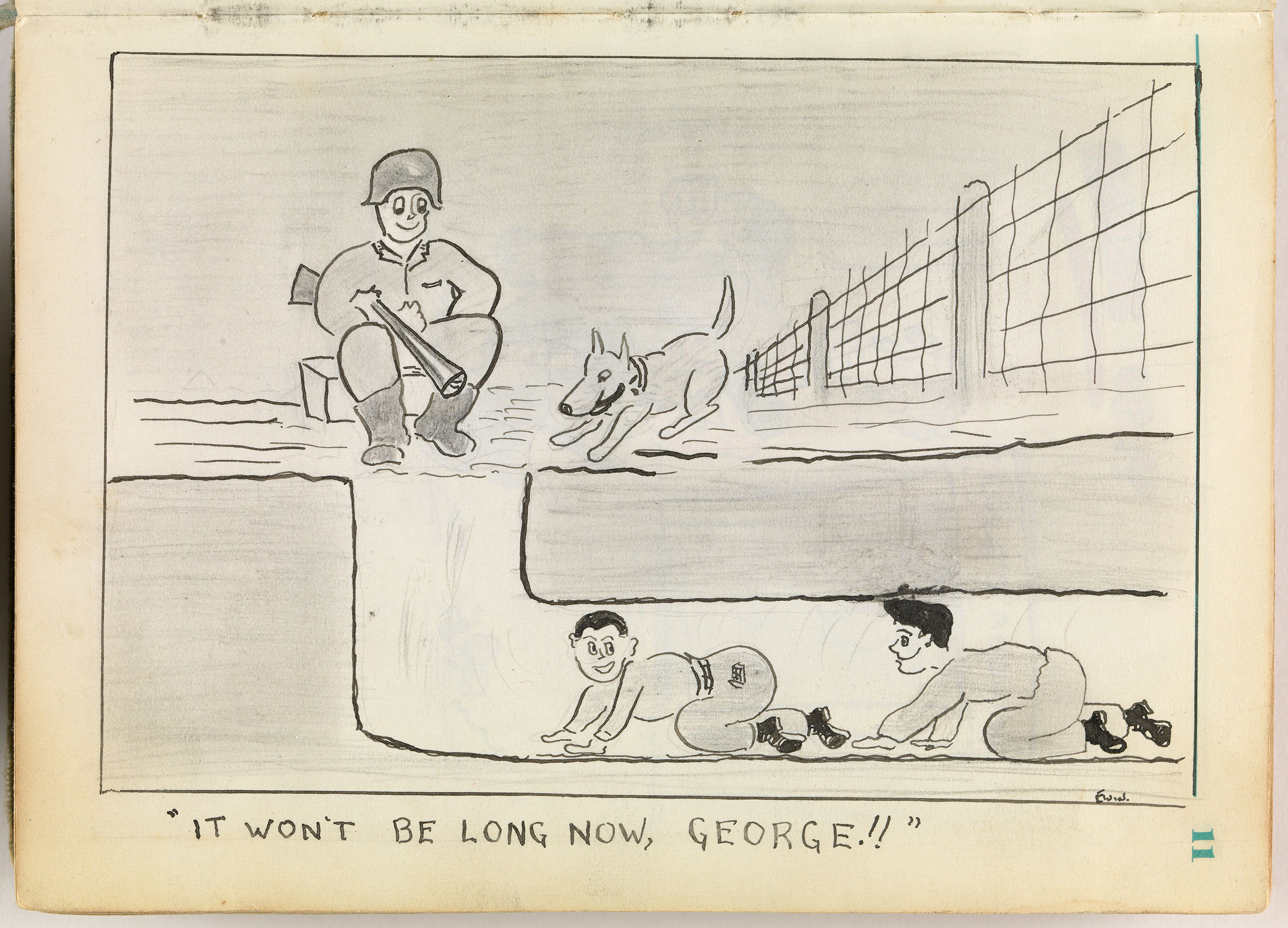

Makepeace finds humour, resilience and despair in the hundreds of documents she has sifted through to bring this book together. She finds amusing moments of quiet rebellion, such as the silky beard competition that followed a ban on razors, the cartoons gently mocking camp optimists and incorrigible escape artists, and a surprising celebration of being shackled: “a great blessing to have an evening meal brought to you without all the fuss and bother of preparing it”. And she finds the defiance and optimism we’ve all been led to expect, with prisoners forming a unique collective identity in opposition to their captors, but also in contrast to the people back home who sometimes pitifully failed to understand what they were going through. But Makepeace also inevitably finds frustration and sorrow as writers lament their wasted youth, “cow-like” existence and distance from home, while attempting to bring it closer through their rich fantasy lives and the ghosts of the distant living that haunted their waking dreams.

A fascinating chapter details how prisoners built and maintained bonds with their fellow captives, finding revelatory evidence of rivalry, division and frustration at odds with the “all-in-it-together” mentality promulgated by mass media. The men used their diaries to vent, detailing a litany of complaints about lazy, selfish, untidy and snobbish fellow-captives, and the inevitable petty quarrels that erupted. It’s not a million miles away from the frustrations of a shared university house. Even more revelatory is the section on female impersonators and their strange, transgressive effect on the masculinity and desires of men long separated from wives and girlfriends. Makepeace’s conclusions about the level of tolerance and pragmatism towards sexuality found amongst prisoners of war are both surprising and thought-provoking.

Perhaps the most exciting thing about Captives of War is the treasure-trove of drawings, photos, cartoons and handwritten diary-entries that Makepeace has uncovered, which give an unprecedented insight into the lives and thought processes of real people who had passed into something approaching hagiography. Witty, silly and sometimes bleak, they are priceless documents of a past we have taken for granted. And in the final chapter, when Makepeace explores how former POWs adapted to freedom and resettlement, she has to do so without the benefit of the diaries, which had been jettisoned by men far too overwhelmed by freedom to write down their thoughts. It’s at this point the reader is hit by what amusing, difficult, resilient, reflective, pained companions these men have been throughout the book, and how much we miss them.

While Captives of War is a captivating, propulsive read (I got through it in one pleasurable sitting) it is very much an academic study, with all the footnotes, appendices and careful objectivity that entails. If it sometimes feels like reading an exceptionally-detailed university essay, well – that’s where it all started, though the depth of research and the flesh that it coats over the bones of these fascinating men in extraordinary circumstances makes it a worthy, revealing study. That annual viewing of The Great Escape will never be quite the same.

Captives of War

Available now in hardback from Cambridge University Press