Ben Olsen explores the 58th edition of the Milan Furniture Fair, and considers whether we really need new things

Words Ben Olsen

Although renowned for its celebration of newness, this year’s Salone del Mobile felt somewhat different. While swathes of visitors, picture-perfect prototypes and countless flashy product launches turned Milan into an aesthete’s paradise for the week, a prevailing mood weaved throughout this excess of exhibitions and installations that struck a positive note for the future.

Across the city, designers and architects were putting sustainability at the heart of their work, championing conscious consumerism and inventive manufacturing solutions – evidence of a shift that’s been a long time coming. “Back in 2009 people saw sustainability as a trend – perhaps in the same way as, say, velvet – but I had a different belief,” says Henrik Marstrand, founder of Danish design firm Mater. “For us there has to be a compelling reason to make any new product, besides the design.”

Ocean Collection, MATER

Mater’s newly launched Ocean Collection is testament to this approach, a series of outdoor tables and chairs based on a 1955 model by Danish designer Nanna and Jørgen Ditzel but with a crucial twist. The raw materials include a significant portion of waste plastic salvaged from the seas. A facility on the west coast of Denmark converts fishing nets into plastic pellets, which are then melted down and mixed with other plastics, with 960g of salvaged plastic used in every Ocean chair. “It’s important you think about the legacy you leave behind,” he says. “We must look at the idea of a circular economy and the second-life of a product. These chairs can be disassembled completely so the plastic and the steel can go into new cycles.”

Conifera, ARTHUR MAMOU-MANI

A similarly forward-thinking approach was seen at Milan’s elegant Palazzo Isimbardi, where French architect Arthur Mamou-Mani showcased the potential of bioplastic with one of Salone’s most striking art installations, presented in conjunction with COS. Weaving its way through the 16th century courtyard into the garden, Conifera is the world’s largest 3D-printed structure, created from a network of bricks made from fully compostable bioplastics. Visually impressive, yes, but its concept also has the potential to be far reaching.

According to Mamou-Mani, the idea of using bioplastic and the minimisation of waste came very early in the concept. “There’s been a human acknowledgement of the need to act now, helped by graphic images of nature suffering and the UN report urging us to lower the carbon footprint,” he says. “What do we do? Do we disappear or do we act now? There is an awakening and we are in a new era.” He claims the material used for Conifera, created from corn starch, has similar properties to plastic but is 68 percent better in terms of its carbon footprint, while his use of 3D-printing technology can show others how best to put bioplastics to good use. “I hope people will see how it’s possible to design with machines and how they shouldn’t be fearful of them. I hope it feels democratic – the machines are affordable and the code behind it is open source. I’m keen to see how it can be used elsewhere in architecture.”

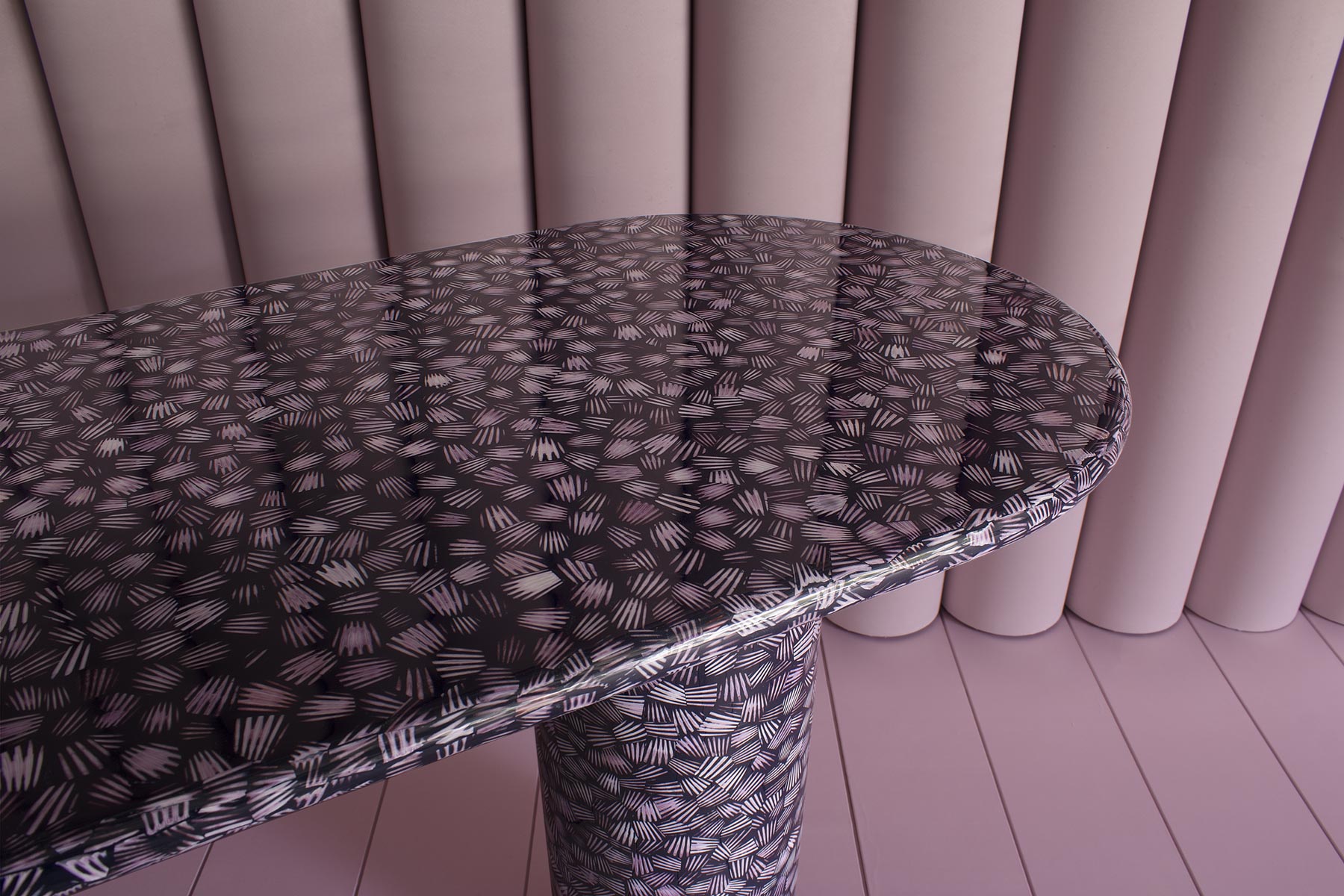

Pink Scallop Shell Desk, BETHAN GRAY

Pearl Shell Fluted Side Table, BETHAN GRAY

It seems the tide is turning. At her beautifully curated exhibition space, Rossana Orlandi’s Guiltless Plastic campaign saw a series of pioneering projects attempting to break our unhealthy obsession with plastic. Elsewhere the concept of a circular economy played out in myriad forms. British designer Bethan Gray’s collaboration with Nature Squared featured the use of discarded scallop and oyster shells and pheasant and hen feathers, each finding a beautiful second life in an elegant range of furniture; Carlo Ratti Associati’s mycelium arches made from an organic fungi-based material took over the Brera botanical garden and many designers employed offcuts from the manufacturing pieces in their work.

Norwegian Presence, KRAKVIK & D’ORAZIO

Another material flexing its eco-credentials at this year’s Salone was aluminium. Strong, flexible, lightweight and 100 per cent recyclable, it’s a true poster boy for the circular economy. The Norwegian Presence exhibition – a multifaceted collective from the Scandinavian nation – featured a series of pieces that put the focus on aluminium, helped by a partnership with Norwegian aluminium firm Hydro. “As a growing trend, we see that aluminium is increasingly used alongside wood in Norwegian products and design due to its beautiful surface, formability and suitability for a circular economy,” says Hydro’s Hilde Haugen Kallevig. “Recycling aluminium only requires five percent of the energy used to produce aluminium the first time, which means the footprint is reduced each time it goes back into the loop.”

Yet for all the right-thinking eco credentials on display, the question remains as to why we, as a society, need new products. The Norwegian Presence collection was curated by Jannicke Kråkvik and Alessandro D’Orazio of design studio Kråkvik&D’Orazio, with the work on show aiming to highlight the economic and social dimensions of circular design. “Why should we design a new thing? In addition to aesthetics, the object must have a value in terms of materiality or durability,” said Kråkvik. “The items we have chosen must give something in return – through longevity, decomposability or the way in which they are produced.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by architect Mamou-Mani, with some urgency. “New for new’s sake, or better for better’s sake – we don’t have the time for that,” he says. “As designers and architects we have great responsibility as it’s us who have to power to choose the materials we use.”