In light of the iconic painter’s recent death, Aindrea Emelife explores the idea that, even in a tech-saturated landscape, the art world will always return to its paintbrushes

Sir Howard Hodgkin, who died this week aged 84, was undeniably one of the most exciting painters of our generation, his confidence in brush stroke, sharp-eyed use of colour and sheer vivacity impossible to mimic. The idea that the last of Hodgkin’s works has been painted is an unsettling thought. And yet, his legacy lives on in the fires he lit within the bellies of today’s abstract painters, forever the King of colour.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of Duchamp’s Fountain crashing into the art world and changing things forever. Since then, we’ve lived in quite a conceptual age. Meaning trumps aesthetic; essays, text and ideas serve as the Rosetta Stone to decode complicated (or often banal) installations and artworks swathed in obscurity. The art world could be forgiven for experiencing a bit of a headache after all that. The cure? Something unfamiliar, yet familiar: the new painters are coming.

In September 2016, Artspace referred to painting as an “ancient art form” in an interview with super-curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist. Ridiculous, I know. But though this article ostensibly argues that we are returning to painting, I don’t actually think painting ever left. It was just quietly waiting its turn, perhaps ageing like a good red wine, while we were distracted by shiny, new technologies and publicity stunts masked as art. Paintings are still often the gateway for people’s initial fascination with art – and to counteract the ADHD art has suffered from lately, it’s time to ruminate over the evocative work of the latest exponents of the form. While the late ‘70s and early ‘80s brought a new spirit in painting – German neo-expressionism, late Picasso, Julian Schnabel and the like – that was all a refresh of figuration. What’s been rumbling lately is an oscillation between figuration and abstraction.

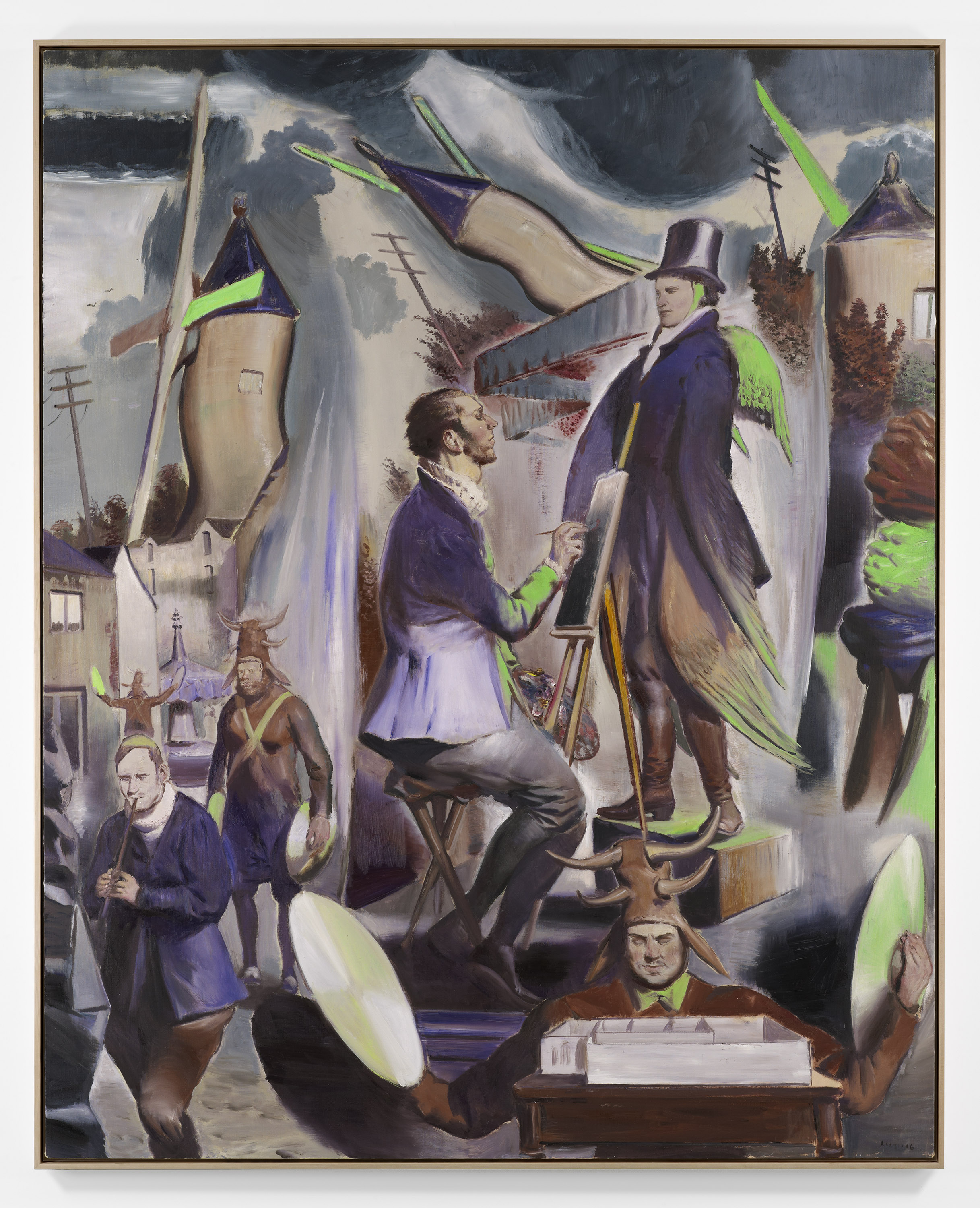

Neo Rauch

Der Auftakt

2016

How did we get here? In the early ‘00s, painting as a medium was widely seen as passé, rendered obsolete by non-traditional approaches to art such as installation, video and interactive participation. But in 2002, New York Times art critic and dedicated keeper of the painting flame Roberta Smith confronted the so-called “death of painting” by coming to its defence in a review of selected shows and flipping the script of dismissal: “The idea that painting is dead is more passé than ever, judging from the medium’s dominance in New York City’s commercial galleries this weekend,” she wrote. In fact, the medium was about to experience one of the most glorious runs of invention since the post-war periods of abstract expression and pop art. Peter Doig, Marlene Dumas and Neo Rauch all made grand entrances and subsequently became staples of our artistic diet. Doig was an especially significant figure: his 2008 Tate Modern exhibition led to a huge surge in his career, just a year after he had become the most expensive living artist in auction with his painting White Canoe.

Melike Kara

To be titled

2016

Even so, in order to truly reincarnate, painting still needed a catalyst to set alight its so-called “outdated mode of representation”. And so we turn back to modernism. That has potential problems: we have, or so I would have hoped, progressed beyond its primitivist idealisations of ‘the other’ and sexist figuration. But neo-modernism, as we can call it, picks and chooses from the styles of the past and adopts the aesthetic as a comment on how much more progress needs to be made in society – or rather, a quite simple, metaphorical ctrl+alt+delete on contemporary art’s over-conceptualism in order to to start anew. An example of this would be Cologne-based artist Melike Kara. Her work To be titled, which featured in Lawrence van Hagen’s What’s Up 2.0 show at 94 Portland Place this autumn, reminds me instantly of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Picasso’s controversial 1907 painting of squatting prostitutes in African masks. Notably, the heavy male figures grimace and stare with Loki-like faces – thus switching the narrative to represent, instead, a confusion of male identity, something omnipresent in today’s society.

Taking from history and re-establishing itself in a modern idiom forms the basis of Genieve Figgis’s work. The Irish artist’s ‘covers’ of famous artworks create a new dialogue with the past. It is more than just rehashing and riffing on past successes: she is drawing our attention back so that we can look forward critically. It’s like putting a ‘contemporary art filter’ on a Greatest Hits of art history. The Swing after Fragonard (2014), for example, is most obviously a response to 18th century French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s landmark work The Swing (c. 1767) – but, as Ben Eastham argued on Artsy.net, also references another famous swing: “The one that American Beaux-Arts architect Stanford White was rumoured to keep in his luxurious New York apartment to in a ploy to seduce young women.” Another parallel can be drawn politically: the original Fragonard painting puts us in pre-revolution France, and this too is a time of political turbulence marked by a sense of the unknown, a foreboding that that something terrible could happen at any given time. Perhaps a shift back into painting reflects an identical political move backwards, as artists use the medium as catharsis for political replay: a painterly déjà vu of sorts. In Mr & Mrs Andrews after Gainsborough (2015), Figgis reinvents the English portraitist’s titular 1750 work to give it a contemporary meaning, as she addresses modern-day issues of land and ownership. This sort of reissuing of historical motifs emphasises that the best art isn’t frozen in time – and functions as a rebuke to the art world and new media artists more concerned with the ‘now’ rather than the ‘forever’.

Howard Hodgkin

Ice Cream

2015-16

Surprise, Surprise

2015-16

Meanwhile, the now late Howard Hodgkin, the father of British abstraction, served up something new with After All, his most recent show at the Alan Cristea Gallery – a mix of paint and print. Works such as Ice Cream are made up of sweet shop pinks and yellows that continue the sensual immediacy and visual intoxication his work has maintained over the years. He may not have invented the technique of layering printmaking and handpainting – but the consistency and variety in the show creates the immersive effect that makes abstraction so endearing. The ambiguity in abstract painting challenges the over-specificity of conceptual art, and while Hodgkin may be the genre’s high priest, his work remains free and youthful – and in line with the new movement we are experiencing now, which is why young artists and viewers relate so deeply.

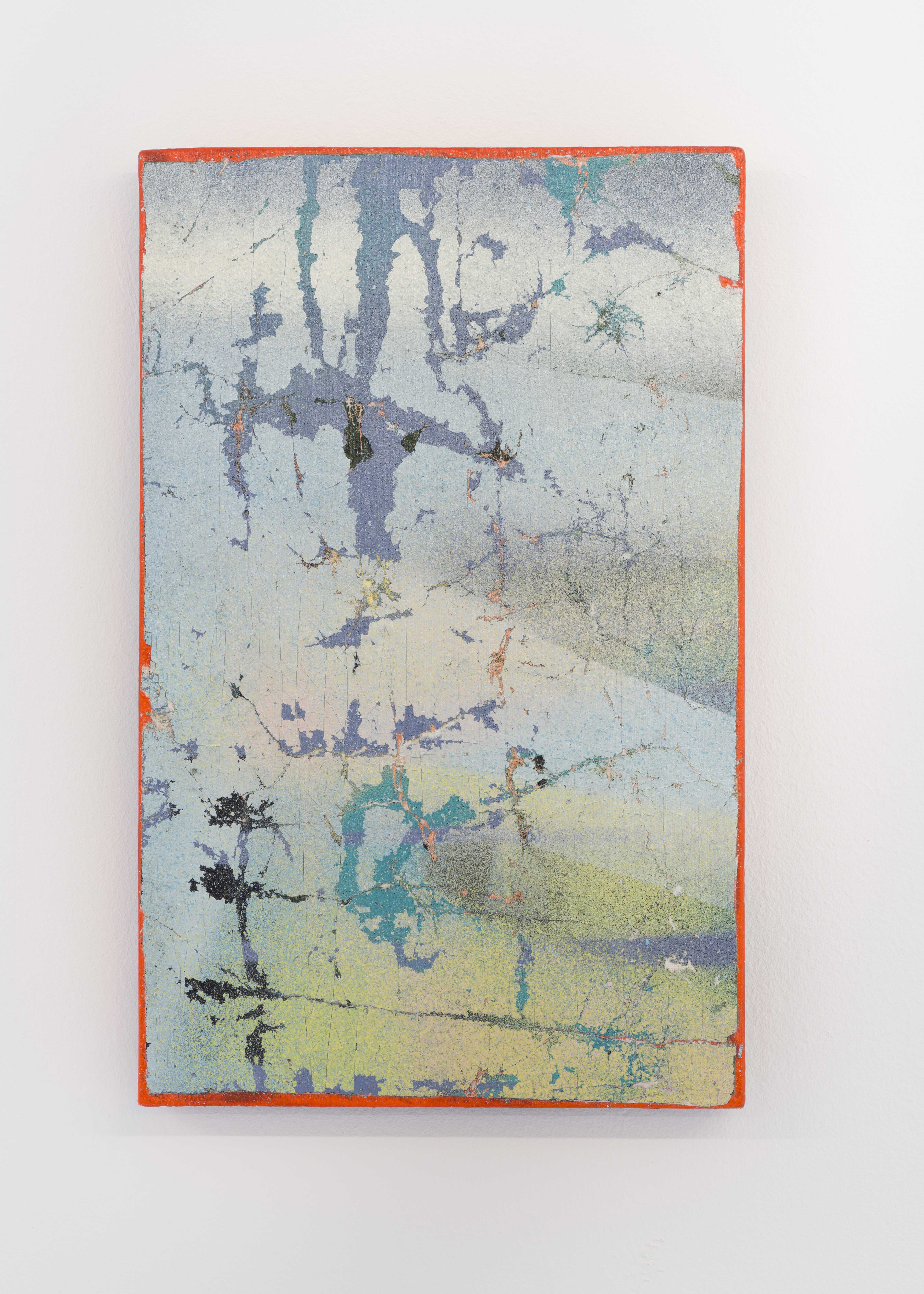

In particular, there are the heirs to Hodgkin’s throne – Peckham princes Shaun McDowell and Christopher Green, of the Hannah Barry Gallery, who are already sending the art world into a tizz with their arresting abstract works. “We are surrounded, even commanded by digital interface at every junction in our lives,” says McDowell. “So the physicality of paint is definitely more, not less important now.” He describes his paintings as being a material render of the modern era’s visual overload: vast, serene but chaotic works such as Navigator – ironically, impossible to navigate – seem to map thoughts and imagery flying through the ether and sucking you into a vortex of information and ideas, a true manifestation of abstract thinking. McDowell muses: “Today, abstraction is a perfect expression. It seems the most logical thing to me. Separate strands of information are absorbed, considered, filtered – expressed in a way that each part is not separate from one another. The ‘sense’ takes shape through colour and line.”

Christopher Green

G-O-L-D-E-N

2013

Endless rain / Paper cup

2013

Carry on, turn me on

2013

It should be said that there are some processes that take “painting for the digital age” down dead ends. I have yet to see a digital painting that moves me, for example. The main advantages of paint are its immediacy and fluidity of colour. Digital painters just don’t seem to hit the same authenticity that hand-to-brush creates. It’s not about backwards-looking traditionalism, but true aspiration now involves escaping the digital and urban worlds. It’s the first time we have hit this tipping point.

Instead, painters are now taking a variety of simultaneous approaches, as shows – both in museums and commercial galleries – oscillate between figuration and abstraction. Every sort of style is happening at once. The idea that there can still be something ‘new’ in painting still seems bold – but why? When television was invented, we didn’t all throw out our radios. So preoccupied have we been with our craving for experimentation that we’ve forgotten new formats aren’t the only means for art to progress. Doing things differently is as exciting as doing something different – and there are still places artists have yet to go, even if the medium has been around for millennia.

Shaun McDowell

Sturm und Drang

2016

Meet the Most Stylish Show-Goers from Day 4 of London Fashion Week AW17

From bloggers to Editors-in-Chief, we round up the best of the street style contingent

Meet the Most Stylish Show-Goers from Day 3 of London Fashion Week AW17

From bloggers to Editors-in-Chief, we round up the best of the street style contingent

Backstage With New Delhi Womenswear Label N&S GAIA, London Fashion Week AW17

The eco-friendly brand presented a painterly, nature-inspired collection for their second catwalk appearance