Swap the dead, white, male Queer British Art for emerging LGBTQ artists

Words Aindrea Emelife

Above: ID 19, Henry Scott Tuke (1858-1929), The Critics 1927, Oil on board, 412 x 514 mm, Warwick District Council (Leamington Spa, UK)

Here’s a shocking fact – it has been only fifty years since the decriminalisation of homosexuality. Yes, most of our parents still remember a time when you could be imprisoned for being a man who loves another man (rumour has it, Queen Victoria insisted that ladies simply didn’t engage in such things). It’s bizarre to think that Elton John was born into that world.

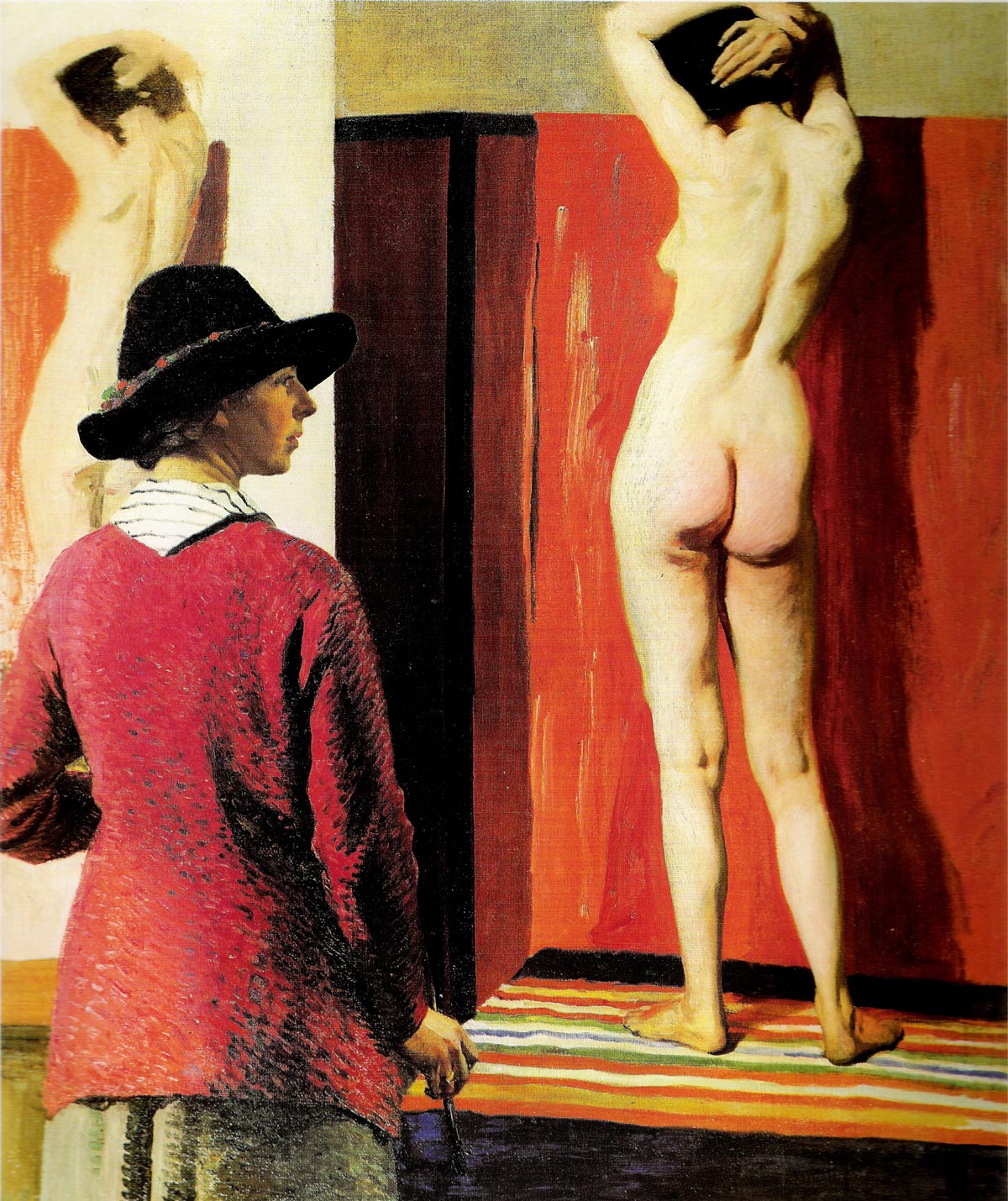

Above: Self portrait and Nude 1913 Laura Knight (1877-1970), Self-Portrait 1913, Oil on canvas 152.4 x 127.6 cm, National Portrait Gallery (London, UK)

To mark this great triumph over injustice, a new exhibition opens at Tate Britain this month, exploring how seismic shifts in gender and sexuality found expression in the arts. Spanning the period from the abolition of the ‘death penalty for buggery’ in 1861 all the way up to full decriminalisation in 1967, ‘Queer British Art 1861–1967’ features notable ‘queer’ painters, illustrators, photographers and filmmakers such as Gluck, John Singer Sargent, Duncan Grant, Dora Carrington, David Hockney and Francis Bacon.

But not everyone is overjoyed with this self-styled celebration of LGBTQ creativity. Last year, following the announcement of the show, writer and media personality Janet Street-Porter took to the Independent to voice her concerns that “our obsession with sexuality is dimming our ability to respond to great art and enjoy it for what it is”. Was fifty years of decriminalisation really a cause of celebration, she wondered, or just a reminder that gender, in its most binary sense, still dominates the way we think, and is now being thrusted upon the way we view art?

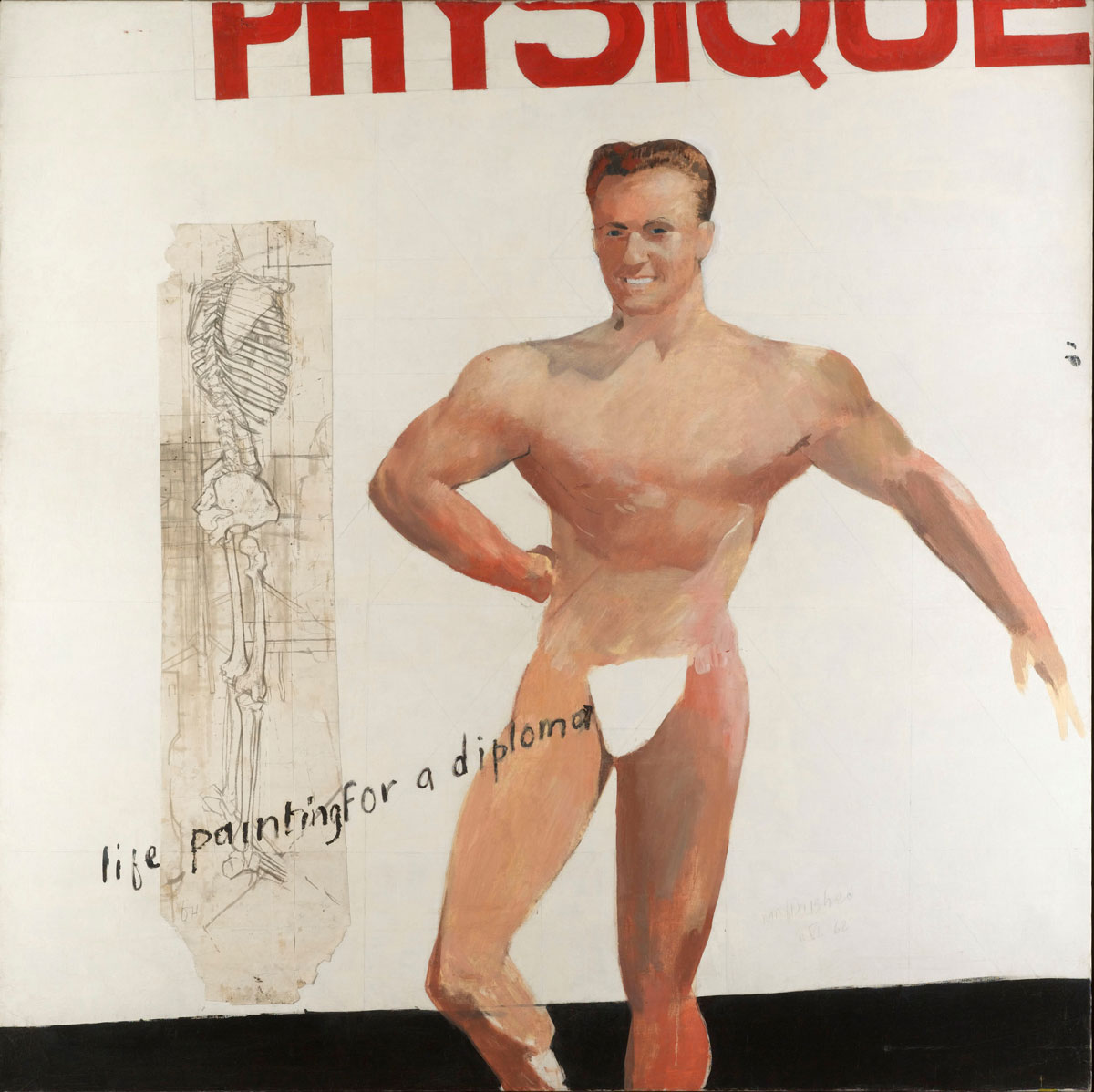

Above: Hockney, David Hockney Life Painting for a Diploma 1962, Yageo Foundation © Yageo Foundation

Our obsession with sexuality is dimming our ability to respond to great art and enjoy it for what it is

She had a point. Lumping together art based on the sexual orientation of the artist looks a lot like lazy curating, just as a show on art by black people with no other unifying theme or justification would meet outrage. Who the artist finds attractive or engages in romantic relationships with does not make them part of an exclusive club that then creates a subconscious unilateral similarity… or at least not from what I can see. Take Hockney – his works, which features in the show, do not speak to me as a comment or reflection on his sexuality, but rather of his love of nature, cities and people. Sure, there are some male buttocks here and there, and yes they are sexualised as they slowly heave, glistening wet, out of swimming pools. But had they been female, and had he been straight, would they be a comment on heterosexuality? I suspect not.

The artists in the show are predominantly male. That is unsurprising – many Tate shows share the same unbalanced ratio – but particularly poignant, when we remember that lesbianism was never deemed real enough to warrant legal punishment. The struggles of gay men are distinctly different to the experience of lesbian women, and indeed everyone else on the spectrum of non-conventional sexuality, and it seems even more problematic to aim to capture a sense of ‘queerness’ when we consider the breadth that ‘queer’ includes.

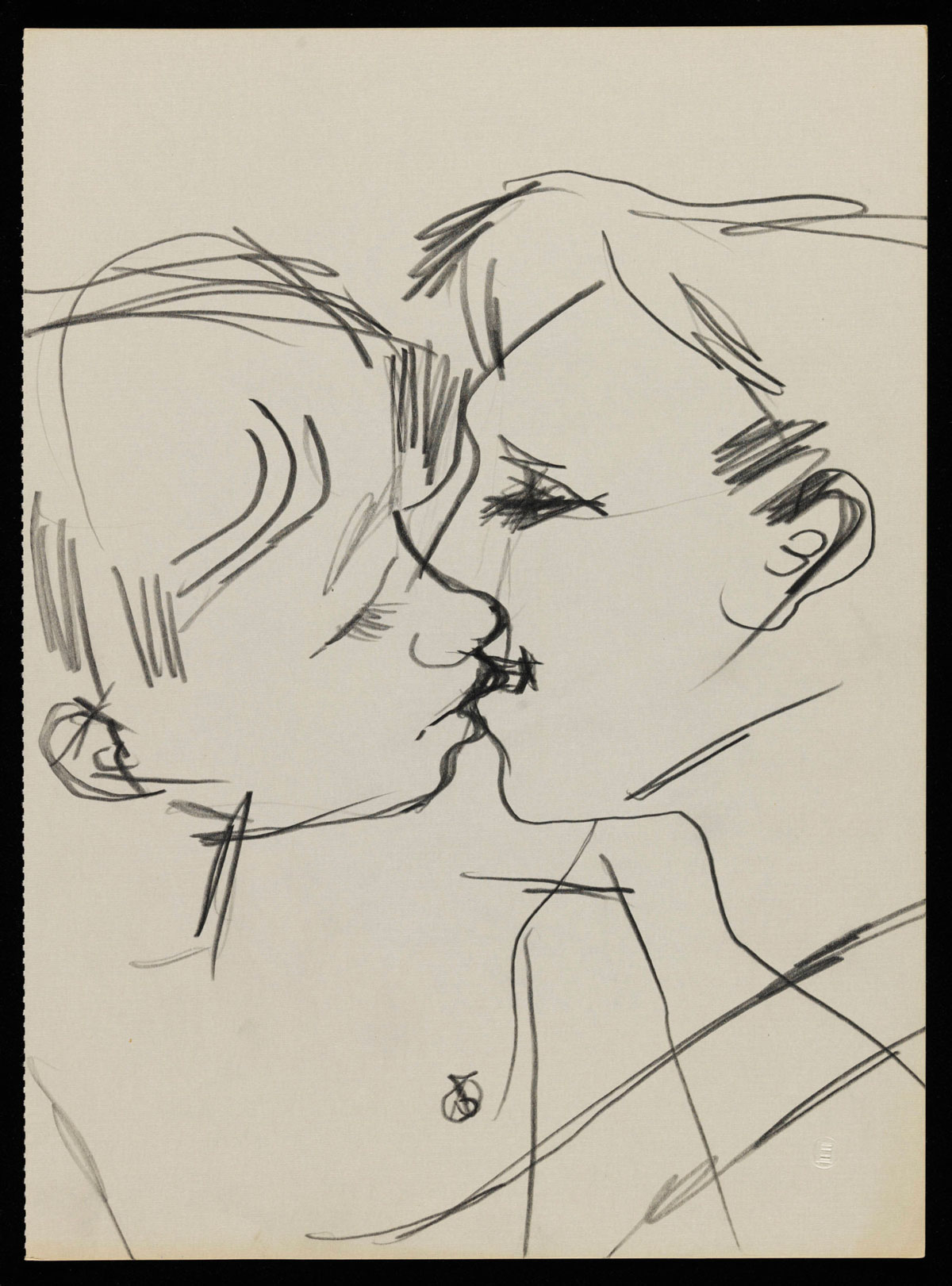

Above: Out, Keith Vaughan, Drawing of two men kissing, 1958–73 Tate Archive © DACS, The Estate of Keith Vaughan

The term itself has a complicated history, as artist Sam Cottington, whose recent work includes a project called ‘Do you even know what a screaming faggot looks like’, agrees. “Arguably the term queer resists clear definition and instrumentalisation into normative institutions by nature of its existence as a critique of normative institutions (e.g. institutions of gender and sexuality)” he argues. “For this reason I think it’s fair to say that the Tate Britain’s use of this term can be seen as inappropriate, even if its intention is toward an inclusivity.”

Nowadays, when most artists and creatives seem to be fighting for a freedom from labels, the very concept of such a show seems regressive. And there’s the problem that, by trying to promote one sort of diversity, you can diminish another. “We are constantly torn between trying to say labels don’t matter and also wearing our labels with pride,” admits artist and activist Liv Wynter. “I identify as queer and a woman, and I am very vocal about that because there aren’t enough of us in the arts. I’ll continue to do all-women shows providing they are accepting of trans-femme and non-binary people, I’ll continue to do queer shows as long as they aren’t dominated by white gays. My issue with the Tate show isn’t the queerness, it’s the whiteness and the maleness.”

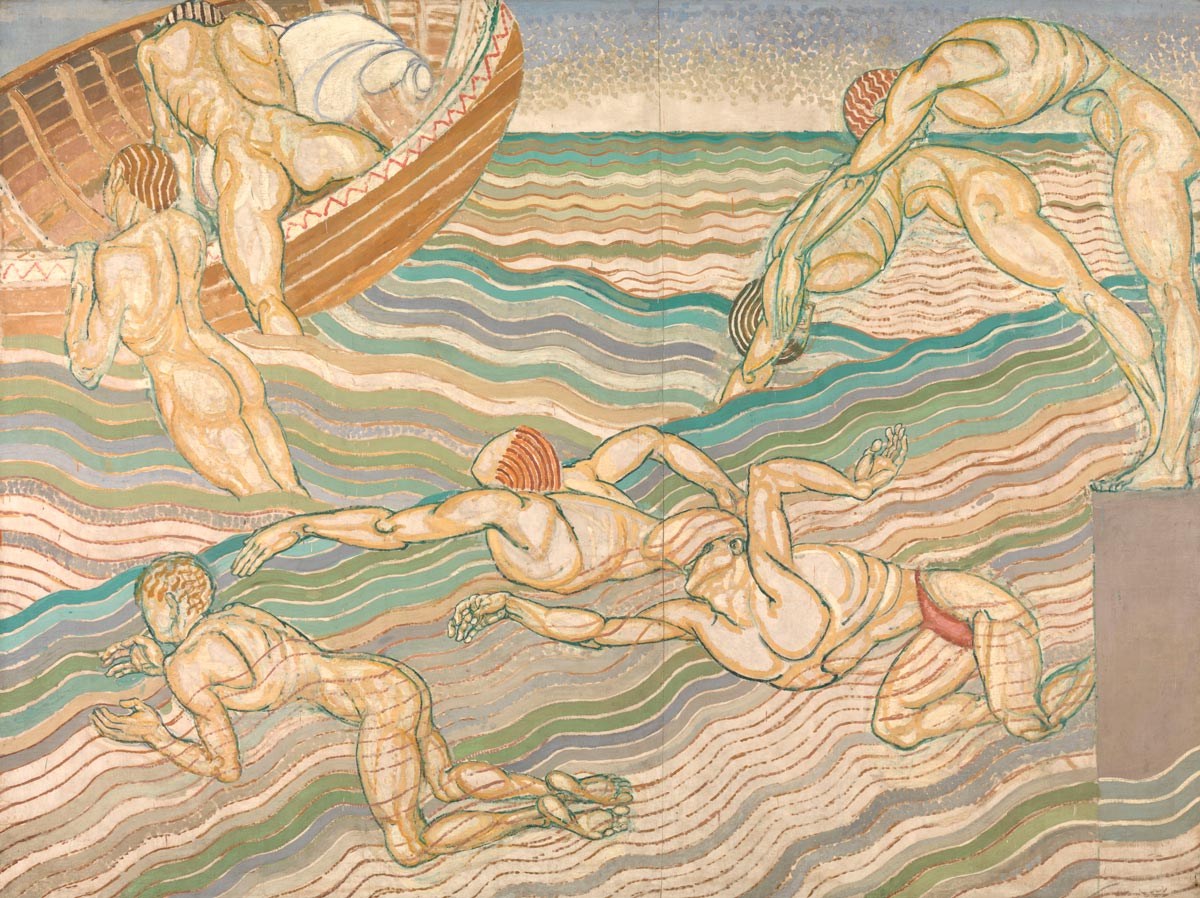

Above: Duncan Grant, Bathing 1911, Oil paint on canvas 2286 x 3061 mm © Tate

Of course, attempts to celebrate difference and acceptance are always good. Gemma Rolls-Bentley, Gallery Manager at Artsy, author, and columnist at Gay Times is thrilled at the idea of the show.“Tate’s upcoming exhibition Queer provides an opportunity to mark changing attitudes in society and to reflect on the historical struggles of the queer community,” she says. “The reality is that LGBTQ+ people all around the world face challenges on a daily basis and their voices are so often underrepresented, which is why it is so important for institutions like Tate to provide a platform to celebrate queer culture, share the community’s stories and shine a light on creative responses to the queer experience.”

Zhoe Granger, Assistant Director of Peckham gallery Arcadia Missa, also feels positive. “What is art if it isn’t generating a sociological discussion – past and present?” she asks. “Queer politics are integral to the world’s history. Would people question a show about colonialism?”

Above: Solomon, Simeon 1840-1905, Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene 1864, Watercolour on paper 330 x 381 mm Tate. Purchased 1980

However, Cottington fears that the definition of queerness will be too narrow. “My fear is whether the show is representative of a broad and less well documented intersectional queer art history.” He is more interested in “research into artists that made valuable contributions to art but were less well documented due to the misogyny, racism, classism or transphobia of the art world. As well as the impact the AIDS epidemic had on the cultural production of a whole generation of gay men, or the way government negligence and violence has impacted the types of work queer people make, and their ability to make work at all.”

So is there any way to explore ‘queer art’ without falling prey to all the usual stumbling blocks? I’d encourage people to look not to big institutional reviews but commercial galleries for a raw, contemporary exercise in understanding sexual politics within the LGBTIAQ+ community. Project Native Informant, a groundbreaking gallery in Holborn, recently showed Hal Fischer’s ‘Gay Semiotics’, taken directly from Fischer’s personal experiences living in the vibrant gay communities of San Francisco’s Castro and Haight-Ashbury districts. It provided a provoking analysis of a gay historical vernacular, as well as a tongue in cheek appropriation of the theories of Roland Barthes and Claude Levi-Strauss.

“We’ve got quite an apt show on at the moment of work that was made after the decriminalisation but before HIV/aids,” Jackson Bateman, from the gallery, explains. “I think it is interesting to think about what liberation meant then and how now identifying as ‘queer’ seems more of a politicised status than anything to do with actual sexuality.”

At least the Tate is trying – and it’s admirable that curator Clare Barlow had the bravery to go ahead with such a show, knowing she would draw flak. Go and see it, but the key is to not stop there. Seek out the work of emerging young LGBTIAQ+ artists and see what their work says to you. If it speaks to you issues of sexuality and gender, fantastic. If it doesn’t, it probably has a lot of others things to say of value. Either way, you’ll be doing your bit to ensure that the artists get the visibility and funding they need, whoever they choose to take to bed.

More from PHOENIX

Meet the Most Stylish Show-Goers from Day 4 of London Fashion Week AW17

From bloggers to Editors-in-Chief, we round up the best of the street style contingent

Meet the Most Stylish Show-Goers from Day 3 of London Fashion Week AW17

From bloggers to Editors-in-Chief, we round up the best of the street style contingent

Backstage With New Delhi Womenswear Label N&S GAIA, London Fashion Week AW17

The eco-friendly brand presented a painterly, nature-inspired collection for their second catwalk appearance