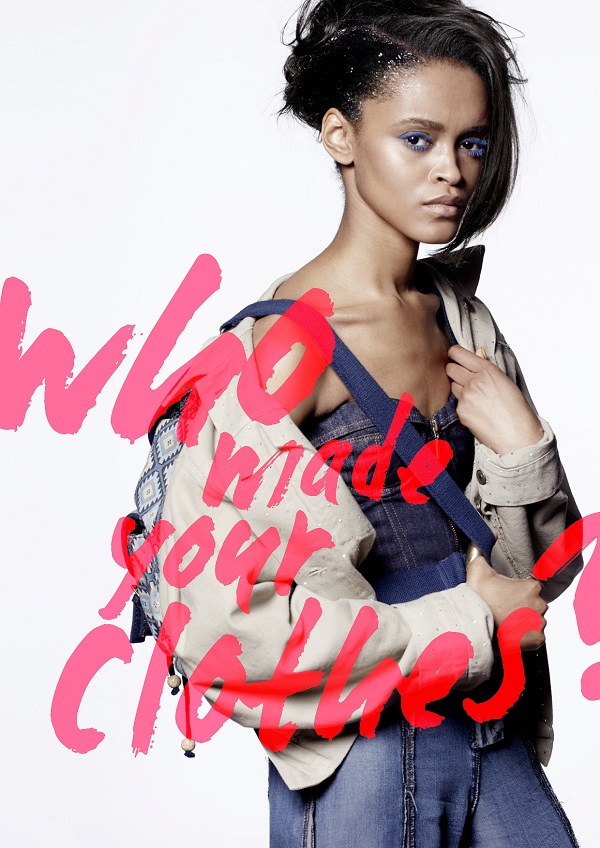

It’s Fashion Revolution Day. Do you know who made your clothes?

On 24th April last year, 1133 people were killed and over 2500 were injured when the Rana Plaza factory complex collapsed in Dhaka, Bangladesh, a catastrophic event that brought the fashion supply chain’s enormous social and environmental flaws under the spotlight.

The #INSIDEOUT campaign strives for greater transparency in the fashion industry, honing a business structure in which people, the environment, creativity and profit are valued in equal measure.

Here, PHOENIX Editor Hannah Kane delves into the issues surrounding traceability, and asks whether the cost of affordable fashion is too high…

First there were the cracks, imperceptible at first, but soon they snaked across the pillars, walls and floors, splitting the concrete open like spoiling fruit and exposing its slender pylon core. Management led workers gingerly from the building. The building’s owner, a heavy-jowled Dhaka thug named Sohel Rana pronounced the structure safe, and that workers were safe to return the next day. Unconvinced, many had little choice. “The factory management threatened the workers that their month’s salary would not be paid if they did not show up at work,” said Shahadat Hossain, the brother of a garment worker in one of the factories.

The next morning, on April 24, 2013, as a generator shuddered to life, vibrations travelled through Rana Plaza, which is situated in Savar in the northwest of Bangladesh’s sprawling capital. These set in motion a chain of structural failures that brought the eight-storey structure to its knees in less than 120 seconds. By the time the dust settled, 1,129 people were dead and almost 2,500 injured. “I was extremely sad when I heard the news about Rana Plaza, but I wasn’t at all surprised,” Safia Minney, CEO of ethical retailer People Tree, told us. “The realities of sweatshops and the poverty in which people live means they are often unable to feed themselves more than a couple of meals a day, often working with only two days off a month and working up to 14 hours a day.”

“Bangladesh brought a lot of attention to the global issue of clothing manufacturing and production, and I think it forced a lot of consumers to think and actually see what they were buying into,” says Jennifer Sharpe, founder of ClothingTraceability.com. The Brooklyn-based designer set up the organisation through “a desire to have more information and provide more information to others on where our clothing was coming from and the implications within that basic idea”. She’s experimented with QR (Quick Response) code labels on her ethical garments that provide the consumer with supply chain information.

There’s no doubt that the information currently available is limited. Say you go into a shop and spot a cute top. If you cared where it was made, then don’t rely on the label for answers. Country of origin labelling is, generally speaking, not compulsory in the EU. A designer handbag from Bond Street, proudly boasting its “Made in Italy” credentials, has more likely been manufactured in China, but may as a consolation prize have had its handle attached somewhere outside Florence. The ever-patriotic Americans are more stringent in this area: “Made in the USA” means the product was wholly manufactured there from fibre to finish.

Most companies do not deliberately set out to hide their sources. In many cases, firms genuinely struggle to unravel the supply chain further back than the final Cut-Make-Trim (CMT) stage. Anti-slavery group Not For Sale’s 2012 FREE2WORK report collated hard data from many of the major global fashion corporations including Abercrombie & Fitch (also group owners of Hollister and Gilly Hicks), Adidas (who own Reebok), Forever 21, Inditex (owner of labels such as Zara, Pull & Bear and Massimo Dutti), Phillips Van Heusen (Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger), Skechers, Timberland, and Walmart (George at Asda). They found that while only 46 percent could fully trace their CMT stage, by the time they looked back into where the textile production occurred (the Input stage), and indeed where the Raw Materials were farmed, only 18 percent could fully trace the suppliers in each category.

Minney has this advice to companies seeking to change. “The first step is to really know where each part of the products are manufactured. You’d start pragmatically thinking, What’s the most value here in the product? Is it cotton? Then: where has this been manufactured? Who has it been manufactured by? What are the conditions in which it has been manufactured?” As consumers, what factors would she ask us to consider when making a fashion purchase? “How political is your magazine?” she counters. “I suppose you have to ask yourself whether you need to buy something new at all. If you do need to buy something new, buy it Fairtrade or buy it ethically made of organic cotton.”

Sharpe weighs in on the debate, “I primarily look at quality and personal aesthetic appeal: does it fit well? Is it comfortable? I want to feel that this garment will last me more than two years at the minimum, that it will be something I can get a lot of wear from and can transition through more than one season.” The irony being that the concept of traditional biannual fashion seasons is now as antiquated as the Jacobean ruff, with high street retailers pushing through up to 50 product drops per year.

As the recession drags on, the idea of looking pretty on payday is tantalising. “We live in a society that is pretty egocentric and this is a very difficult time for people, not just in developing countries but in developed countries,” says Orsola de Castro, Curator of the British Fashion Council’s sustainable arm Estethica and Founder of luxury up-cycle label From Somewhere. “It’s gone against us this depression, because people are very concerned about spending less money, so they don’t really care.” For her, provenance is important, but quality is vital.

“It’s the fact that sustainability gets shoved down the drain if people are making really cheap products, because they make compromises,” the pink-haired grande dame of print Zandra Rhodes told us. “If you’re not doing a really cheap product then you aren’t really having to make the same compromises.” Unfortunately, humans tend to be the lowest common denominator in fashion supply chains. “It’s an industry that doesn’t care about people by forcing prices to be cheaper and cheaper year on year,” says Minney.

Rhodes considers whether our failure to make ethical purchases is indicative of ignorance… or apathy. “I don’t think general consumers are aware of anything of those ethical things. Not unless they are very militant. If they care at all they might try to consider ethical attributes, but it depends on what their pocket says,” she says. For Rhodes, the key to sustainability is making no compromises on design: at 73, she’s just designed her first eco collection in partnership with People Tree. “I thought they made a very nice product that would look nice with my things.”

“It is absolutely important that an eco product is desirable. If it is not desirable and functional then no matter how eco it may be, it serves no purpose,” concurs the London-based designer Ada Zanditon. In fact, when we first encountered Zanditon’s fantastical, avant-garde creations several years ago we had no idea she was an “ethical” designer. “Let’s be clear: there are not two separate fashion industries and I personally am not a fan of the term ethical fashion. Simply, there is fashion, and some of it is made more ethically than the rest.”

It is easier for small design labels to monitor their supply chains, de Castro explains. “The nature of being a young brand? You are often sustainable because you have to be. You’re likely to produce locally and be using off-cuts.” Zanditon is a case in point. “The garment itself is easy to trace as it begins its lifecycle in my studio from my design sketch and pattern. I take the fabrics, trims and patterns to the small units I work with, most of whom are in London, and talk to them directly about how to make the designs. They manufacture it, I pay them, collect, and quality check it. It’s that simple. The unique pieces I’m commissioned to create are sometimes made in the studio itself.”

So what does the UK’s place in the sustainability landscape look like? “Sometimes you need to look back not forward,” says de Castro. “I see the return of artisanship and craftsmanship as a tool, not just for the consumer but for the luxury industry overall. I see a return to smaller businesses and identifiable places where you can buy, be it local shops round the corner or your local website round the corner.” You only have to look at the popularity of TV shows such as The Great British Sewing Bee to glimpse the UK’s huge community of makers. Lifestyle brands such as Anthropologie are holding sewing classes, and cult company By Hand London cuts out the middleman altogether, selling sewing patterns and kits to crafty East End hipsters.

The plan, though, isn’t to boycott meaningful trade with the developing world. Fashion trends follow food. First there was organic, then came Fairtrade. Now there’s provenance, a delicious word that describes knowing the source. In a world of equine meatballs, public outcry means you can now go into the supermarket and find the name of the farmer who raised your stewing steak stamped on the packet. Post-Rana Plaza, let us at least be conscious of the invisible fingerprints left on our seams.

Get involved with the Fashion Revolution campaign here.