★★★★☆

Can Alain de Botton’s latest book helps us to develop healthier news-reading habits?

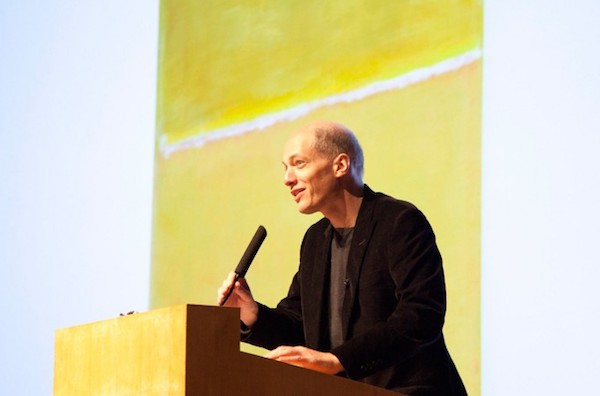

It’s Sunday morning, and in an uninspiring lecture hall somewhere in the boondocks of Bloomsbury, bestselling popular philosopher Alain de Botton is teaching us how to read a newspaper. He brings up a slide showing a photograph of a glacier crumbling into the sea, then flicks to a photograph of Taylor Swift in a pair of shorts walking along a sunny LA street. One is news, the other is not. But why? And how, as a society, can we rise above our Twitter-fuelled deluge of real-time ephemera and use news to become better people, and think deeply about the issues that really matter?

De Botton has a new book to flog, and it makes sense that he should flog it at one of the School of Life’s brilliant Secular Sermons, a monthly gathering – complete with Lady Gaga hymns and themed biscuits – at which earnest young hipsters and earnest mid-life self-developers listen to the likes of David Baddeil on Fame or Mary Anne Hobbs on Love and Loyalty. De Botton founded the School, which gives people “a place to step back and think intelligently about central emotional concerns” via lectures, workshops, books and products, in 2008, and The News: A User’s Manual is exactly the kind of lightly controversial, culturally zeitgesity fare that regular attendees adore.

If you bookend your day with compulsive glimpses at the BBC News app or spend guilty lunch-hours bingeing on the Mail Online’s Sidebar of Shame, de Botton’s manual makes uncomfortably acute reading. Promising “to bring calm, understanding and a measure of sanity to our daily (perhaps even hourly) interactions with the news machine”, he analyses 25 classic news stories to prove that most ‘breaking exclusives’ are in fact the same old archetypes served up in different wrappers. Envy is fed; fears are resurfaced; relief washes through us when we witness that it is someone else’s turn for disaster today.

“Yet there is a particular kind of pleasure at stake here too,” writes de Botton.“The news, however dire it may be and perhaps especially when it is at its worst, can come as a relief from the claustrophobic burden of living with ourselves, of forever trying to do justice to our own potential and of struggling to persuade a few people in our limited orbit to take our ideas and needs seriously. To consult the news is to raise a seashell to our ears and to be overpowered by the roar of humanity. It can be an escape from our preoccupations to locate issues that are so much graver and more compelling than those we have been uniquely allotted, and to allow these larger concerns to drown out our own self-focussed apprehensions and doubts. A famine, a flooded town, a serial killer on the loose, the resignation of a government, an economist’s prediction of breadlines by next year; such outer turmoil is precisely what we might need in order to usher in a sense of inner calm.”

In other words, news addiction serves a very real purpose, and we should not feel ashamed. We should, however, reflect on the feelings that that interview with Natalie Massenet evokes in us, and try to use them to make us healthier and happier, rather than just stewing in envy. For example, a more rewarding approach might:

– Seek out more complex, historic stories such as climate change, or the culture of Iraq, and find ways to make them part of everyday conversation

– Use art, from paintings to theatre, to direct us to deeper more stimulating spiritual, cultural and emotional ‘news’ that is always relevant to humankind; and use art to make difficult subjects sexier and more palatable

– Consider issues through the lens of a number of different biases – say, imagining what Miley Cyrus twerking would mean as part of the Buddhist Noble Eightfold Path

– Rather than feeling guilt about our obsessions with celebrities, accept that role models are important – but understand which of their qualities we would really wish to emulate

– Seek out good news so we get a better balance with the bad

The book is far from perfect. It has stirred up a hearty ripple of controversy in the news organisations it both implicitly and explicitly criticises – surely one of de Botton’s intentions. Reviewers have condemned it as “simplistic” for swapping probing research in favour of obvious platitudes; The Sunday Times‘ Dominic Lawson complains that “de Botton talks about the entire industry as if it were homogenous. It is extraordinarily diverse, more so than ever.” Indeed, such a short volume cannot hope to fully address the nuances of the questions the author raises, and his failure to acknowledge many of the positive practices and innovations being used by organisations such as the BBC is galling to a generation of journalists and broadcasters who have deep integrity in their work, and who are already being squeezed on all sides.

But de Botton’s writing is witty and lucid, his examples eclectic, and his focus refreshingly practical. And his accompanying website, The Philosophers Mail, which rewrites real-time tabloid headlines to give us a glimpse of what a more theraputic model of reporting might look like, is a work of disruptive genius.

This is an important book. Love it or hate it, has the capacity to stimulate some touching conversations about your own hopes and…oh, wait. I’ve just seen that Opening Ceremony is trending on #NYFW. Better go.

If you’d like to receive an elegant signed bookplate especially designed to fit into de Botton’s new book, email your retail receipt together with your address to siobhan@senecaproductions.com using the subject header ‘Bookplate’.

Words: Molly Flatt